With milestones like Tunji Adeniyi-Jones’ Celestial Gathering (2024) topping the sales chart at Art SG for an impressive $350,000 in January 2025, and the launch of Africa Basel, a platform dedicated to presenting contemporary African art in a more intentional, close-knit format, the spotlight on African art has never burned brighter. Across the continent and on the global stage, African art is no longer just a fleeting engagement: it is a growing site of capital investment. Collectors, institutions, and private investors have shifted from asking whether African art matters to actively seeking ways to participate in its ascent.

This momentum is far from accidental. It is the result of decades of layered work—by artists pushing aesthetic boundaries, curators challenging institutional norms, and galleries building infrastructure where little existed. This article traces that shift: what’s fuelling it, who is shaping it, and where it may lead. Drawing on interviews with galleries at the heart of the ecosystem and current market analysis, we explore why African art has emerged as one of the most compelling and credible asset classes in today’s global market.

Global Recognition and Local Brilliance Are Driving Value

The rising global value of African art is no longer a trend, it is a correction of long-standing exclusion and an affirmation of enduring excellence. As artists, galleries, and collectors expand their reach and redefine narratives, a confluence of cultural, digital, and economic shifts is placing African art at the heart of global attention. From global fairs to public installations, artists are not only achieving outstanding acclaim, they are reshaping how the world sees African creativity.

Yinka Ilori’s 100 Found Objects, installed along Fulham Pier in London, symbolically connected Africa and the UK through design, flora, and postcolonial history. Meanwhile, Efie Gallery’s exhibition time heals, not just quick enough…, curated by Ose Ekore and featuring names like Aïda Muluneh and Samuel Fosso, highlighted a curated vision of pan-African identity on the international stage.

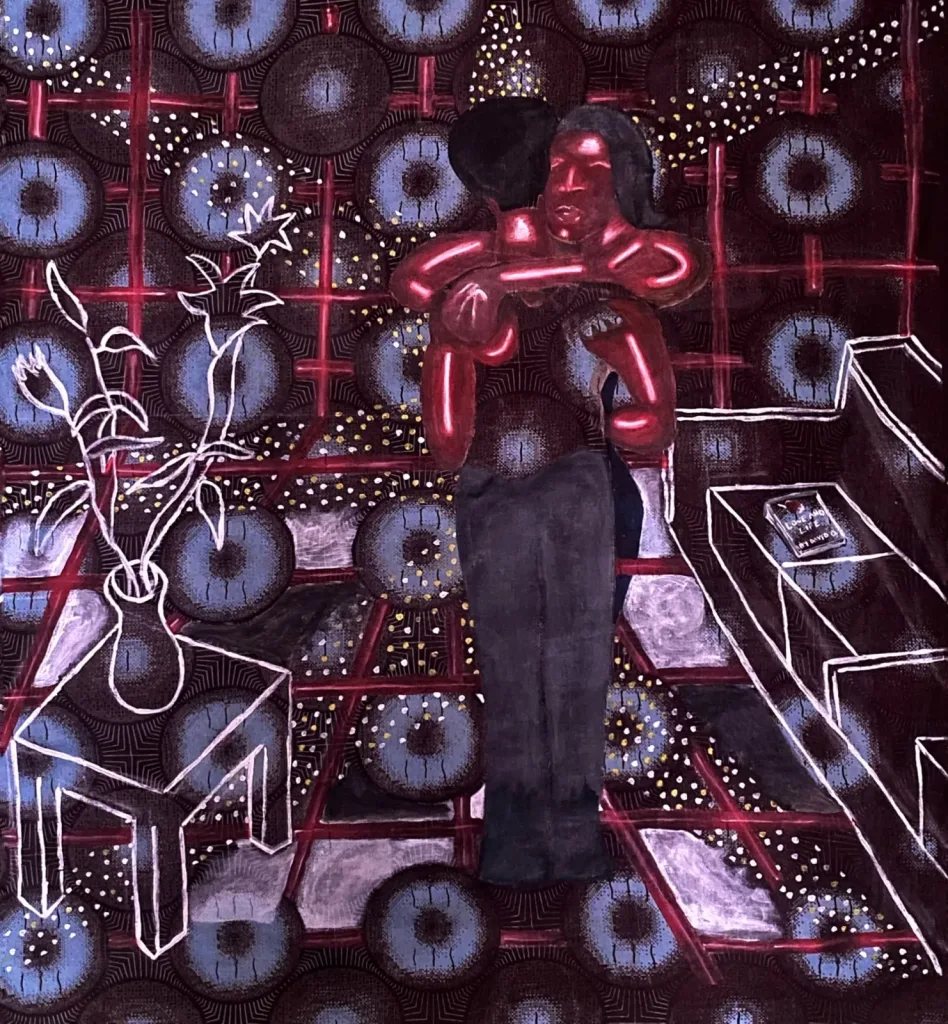

Individual artists are also expanding the boundaries of recognition. Amoako Boafo continues to break ground not only by transforming Gagosian’s Grosvenor Hill gallery into a recreation of his childhood courtyard, but also through his space-bound Suborbital Triptych series launched on Jeff Bezos’ rocket. Each launch includes charitable donations to causes in Africa. Similarly, Boafo’s work Blank Stare was recently acquired by Tate during the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in Marrakech. Other artists to watch include Nigerian artist Deborah Segun, whose vibrant cubist expressions of femininity have captivated global audiences, and Moroccan artist Touils, both of whom earned spots on Maddox Gallery’s 5 Contemporary Artists to Watch in 2025 list. Their inclusion marks a generational shift in how African aesthetics are defined and received.

Crucially, this wave of recognition is not just institutional—it’s digital. Platforms such as Instagram, Artsy, and Latitudes Online have given African artists unprecedented autonomy and global visibility. More localized and artist-founded efforts like Usurpa Africa, the 1111 Augmented Reality Art Project, and Yusuf Aina’s NFT Ainavation exemplify how innovation is fueling access and engagement. Meanwhile, Beyond the Seen, a digital exhibition curated by OSENGWA’s Seju Alero Mike for Harvard Divinity School, showcased multidisciplinary works by African artists and explores the dynamic intersection of art, spirituality, and technology, reminding audiences that African art is as intellectually robust as it is visually striking.

At the curatorial level, institutional backing continues to grow. The upcoming Nigerian Modernism exhibition at the Tate (October 8, 2025 – May 10, 2026) revisits post-independence creativity with works from Uzo Egonu, Ladi Kwali, El Anatsui, Ben Enwonwu MBE, and others. Spanning networks across Zaria, Lagos, Munich, and London, the show cements Nigeria’s modernist legacy within global art history.

Gallery Perspectives

According to Cynthia Okoro, Associate Director at the Rele Gallery, this global recognition is the result of “layered, long-term efforts” motivated by artists, curators, institutions, and collectors. She highlights how figures like Okwui Enwezor and Bisi Silva redefined the global gaze, and how initiatives like Rele’s Young Contemporaries program create sustainable ecosystems for emerging talent. She also highlights how institutions such as the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa have made massive strides: “these spaces are narrative interventions,” she explains, “through which we are able to bring our value systems directly into global art circuits.” Cynthia also points to a growing cohort of African and diasporic collectors who are “acquiring with purpose and vision.” They are not just speculating, but building legacy.

Ally Martinez, curator at the THK Gallery, echoes this: “The rising global value of African art today is, in many ways, a correction of historic exclusion.” She credits Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta11 as a turning point that reframed African art not as peripheral, but as foundational to global contemporary discourse. Yet she emphasizes the importance of viewing African art for its aesthetics and ideas, not just its geography.

Shamiela Tyer, founder of the Eclectica Contemporary, sees a convergence of forces: “sustained institutional interest, high-profile museum exhibitions, increased visibility through art fairs and biennales,” and the rise of a “digitally savvy generation of African artists.” For her, the global market is responding to how these artists engage with both local realities and universal themes.

From a market perspective, Ed Cross, Director at the Ed Cross Fine Art, offers a candid take: “There has been a lot of speculation and we are feeling the consequences of that as the market cools now.” He also notes that with the global institutional support for artists like El Anatsui and Ibrahim Mahama, African art can no longer be sidelined, and the market is completely transformed.

The 2025 Knight Frank Wealth Report reinforces this narrative by acknowledging the growth of the South African art market. African artists such as Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Amoako Boafo have reached auction milestones of $4.7 million and $3.4 million, respectively. Meanwhile, platforms like Strauss & Co. are sustaining momentum both within and beyond the continent, recently recording over $1 million in sales across seven February auctions—underscoring the financial credibility of the South African art market.

Galleries Are Shaping Demand and Building Trust

Behind the rising global visibility of African art lies the steady, often invisible labour of galleries: curating, educating, advocating, and cultivating both artists and audiences. These institutions are not simply commercial intermediaries. They are architects of the art ecosystem, shaping taste, building collector confidence, and grounding cultural narratives within evolving market structures.

In early 2025, this work received notable recognition. South Africa’s Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa topped Curatory Magazine’s list of Five Art Spaces to Watch in 2025, a symbolic nod to the institution’s growing influence beyond the continent. Similarly, Morocco’s Loft Art Gallery earned a spot on Artsy’s shortlist of breakthrough spaces, together with established global names like Saatchi Yates and Nonaka-Hill, for its bold expansion and resilience in a tightening economy. These recognitions point to a shift in perception: African art spaces are no longer playing catch-up; they’re setting the pace.

For the Rele Gallery, this pace has always been intentional. “Galleries are more than intermediaries, they are ecosystem builders,” says Cynthia. “Especially in the context of African art, we operate with a dual mandate: to nurture artistic practice and to build the conditions for its long-term sustainability.” At Rele, curatorial breadth is part of that foundation. The gallery embraces a wide spectrum of artistic forms—performance, textiles, installation, refusing to segregate conceptual from material or ‘art’ from ‘craft.’ This expansive approach not only supports diverse practices but affirms their full cultural and formal complexity: “We present these practices without apology or footnote,” she notes.

Trust, for Rele, is cultivated through consistency: in curatorial quality, institutional placements, artist development, and collector education. “Investor confidence follows when a gallery demonstrates curatorial depth, career stewardship, and consistency,” she explains. “Through exhibitions, institutional placements, critical texts, and collector education, we frame value in a way that resonates across markets and contexts.”

They also play a pedagogical role, which is key. “When a collector engages with an artist through a solo show a publication, or a public programme, they’re not just acquiring a work, they’re entering into a narrative. That narrative is what sustains value beyond the moment of sale.” Central to Rele’s approach is the Young Contemporaries programme under the Rele Arts Foundation, which has run alongside the commercial gallery since its inception. This initiative blends mentorship, visibility, and market-readiness; it nurtures artists into sustainable careers and modeling what holistic support can yield.

At the THK Gallery, the work of trust-building takes on a similarly layered form. “Galleries play a central role in shaping market demand and investor confidence in African art,” says Ally. “They act not only as advocates but as cultural interlocutors—creating platforms that contextualize and elevate artistic practices from the continent.” For THK, credibility comes through long-term investment: “When galleries invest in sustained, long-term relationships with artists, they send a clear signal to the market: these are not momentary fascinations, but vital voices within the contemporary art ecosystem.” That commitment, the gallery stresses, is what allows careers to grow beyond speculative interest into enduring cultural and economic value. In her view, this reframes the art historical canon, placing African art not on the margins as niche or emerging, but at the center of global dialogue.

Indeed, in a market still in the process of correcting decades of underrepresentation, the work of galleries is not just market-making, it’s memory-making. By anchoring artists within institutional circuits, educating collectors, and creating consistent platforms, African galleries are building not just trust, but legacy.

Art Fairs Are Catalysts for Global Validation and Market Access

Once seen as peripheral to the global art market, African art now commands growing attention on the international stage and art fairs are a key force behind that shift. As platforms where visibility, valuation, and validation intersect, fairs offer African artists and galleries vital access to collectors, curators, and institutions worldwide.

According to the Art Basel & UBS Art Market Report 2025, Africa registered an uptick in art fair activity, rising from five to six annual fairs across the continent. More telling than the numbers, however, is the presence of African galleries and artists in globally influential fairs: Art Basel, Frieze, Art SG (Singapore), Art Dubai, The Armory Show, and beyond. Their visibility is steadily redefining what—and who—the global art market values. Complementing this presence are fairs with a dedicated African focus: the transcontinental 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, ART X Lagos, FNB Art Joburg, RMB Latitudes, +234 Art Fair, the Investec Cape Town Art Fair, and others. These events are helping to reposition African art not as a fringe interest but as a compelling and competitive force across global collector circles.

Emerging from this momentum is Africa Basel, a new boutique fair which debuted on the 16th of June, 2025, dedicated exclusively to contemporary African art. With just 20 participating galleries, the fair offers a focused, highly curated platform that fosters meaningful relationships between artists, collectors, and curators. “We believe the era of mega-fairs is drawing to a close,” Benjamin Füglister, one of the Founders of Africa Basel notes, and they’re advocating for a streamlined, intentional model. By designing for intimacy and long-term ecosystem growth rather than sheer scale, Africa Basel hopes to address market volatility and reinforce structural support for the continent’s art economy.

Recognition of African galleries at these fairs continues to grow. During London Gallery Weekend, Prazzle spotlighted Tiwani Contemporary’s In Focus Introduction exhibition For want of a horse, a button was lost by Felix Shumba, alongside blue-chip gallery Perrotin, as a must-see exhibition space. Such moments of parity send a strong signal: African galleries are not just showing up; they’re standing shoulder to shoulder with global heavyweights.

Meanwhile, artist representation in major biennales is also benefitting from this rising fair circuit. At the upcoming 36th Bienal de São Paulo (September 6, 2025 – January 11, 2026), Morocco’s Loft Art Gallery will present Amina Agueznay and Malika Agueznay under the Bienal’s theme, Not All Travellers Walk Roads – Of Humanity as Practice. Drawing on metaphors of water and migration, the Biennial explores connection, coexistence, and the wisdom embedded in oral traditions and non-Western cosmologies. That African artists are active participants such international conversations is evidence of fair exposure translating into long-term cultural and institutional visibility.

Still, the Rele Gallery cautions against a surface-level understanding of art fairs. “International art fairs are undeniably important, but it’s crucial to understand them for what they are,” Cynthia states. “First and foremost, they are commercial vehicles. Their primary function is to facilitate sales and connect galleries with collectors.”

That said, when approached with intention, art fairs can be transformative. “For African galleries and artists, participation in fairs like 1-54, Art Basel, Frieze, and The Armory Show offers more than market access; it offers narrative positioning,” she explains. “It’s an opportunity to collapse the notion of ‘African art’ as a category and instead assert it as a diverse, dynamic, and intellectually rigorous field.”

Rele views fairs not as endpoints, but as entry points—ways to integrate artists into a broader, long-term strategy: “Beyond the booth, we invest in the critical framing, curatorial coherence, and institutional dialogue that make a fair presence impactful.” When grounded in care, rigor, and long-view thinking, fairs can indeed help African art emerge as a viable asset class—not only commercially, but culturally.

Collectors Are Learning to Buy With Purpose

From collecting as status to collecting with soul, what once tilted heavily toward speculation is now balancing with sustainability, personal narrative, and cultural responsibility. Increasingly, collectors are asking not just what to buy, but why.

As noted in an article by Business Day’s Wanted magazine, Lucy MacGarry of Latitudes Online observes a growing wave of values-based collecting: People are being more intentional with their purchases—buying, for example, only female artists, or artists from their own region. Many are supporting underrepresented voices, collecting with a sense of cultural pride, and investing in African art as a way of contributing to a more equitable global art ecosystem.

This ethos is playing out on international stages. The Omenaa Art Foundation, founded by Omenaa Mensah, is one such platform that invites collectors into meaningful engagement with African art. At the Top Charity Auction 2025, held at the Wilanów Palace in Poland with guests including Dr. Jill Biden and Will Smith, African artists took center stage. This reinforces that collecting African art is not just fashionable, but foundational to the global art dialogue; ultimately, the auction raised over €14 million.

Meanwhile, the profile of who collects is also transforming. Roberta Coci, also of Latitudes Online, identified that the traditional art buyer who is typically older, affluent, and already embedded in the art world is evolving. Today, we’re seeing younger, and more diverse and digitally native collectors in the market. Many of these collectors are first-time buyers, less concerned with pedigree and more drawn to emotional connection and online accessibility.

Social media has accelerated this evolution. By providing unfiltered access to artists’ voices, practices, and philosophies, it has democratized entry into the collecting world. Collectors today are often as invested in an artist’s worldview as they are in the artwork itself. Meaning has become currency.

That kind of meaningful engagement is echoed in the guidance galleries are offering to collectors navigating the landscape with intention:

“Buy with both your brain and your gut,” advises Shamiela of the Eclectica Contemporary. “Do your research, understand the context, the artist’s trajectory, and exhibition history. Engage with galleries and curators who specialize in African art rather than chasing market noise. Long-term value is built through informed, thoughtful acquisitions, not trends.”

“Focus on the practice and the intellectual underpinning—ignore the hype,” adds Ed of the Ed Cross Fine Art, emphasizing depth over spectacle.

In a world where collecting can be both a personal journey and a cultural responsibility, the most resonant advice may be this: buy what moves you, but understand what sustains it. Sustainable collections are not built on speculation—they’re cultivated through curiosity, care, and a willingness to learn.

The Future of African Art Is Expansive and Locally Rooted

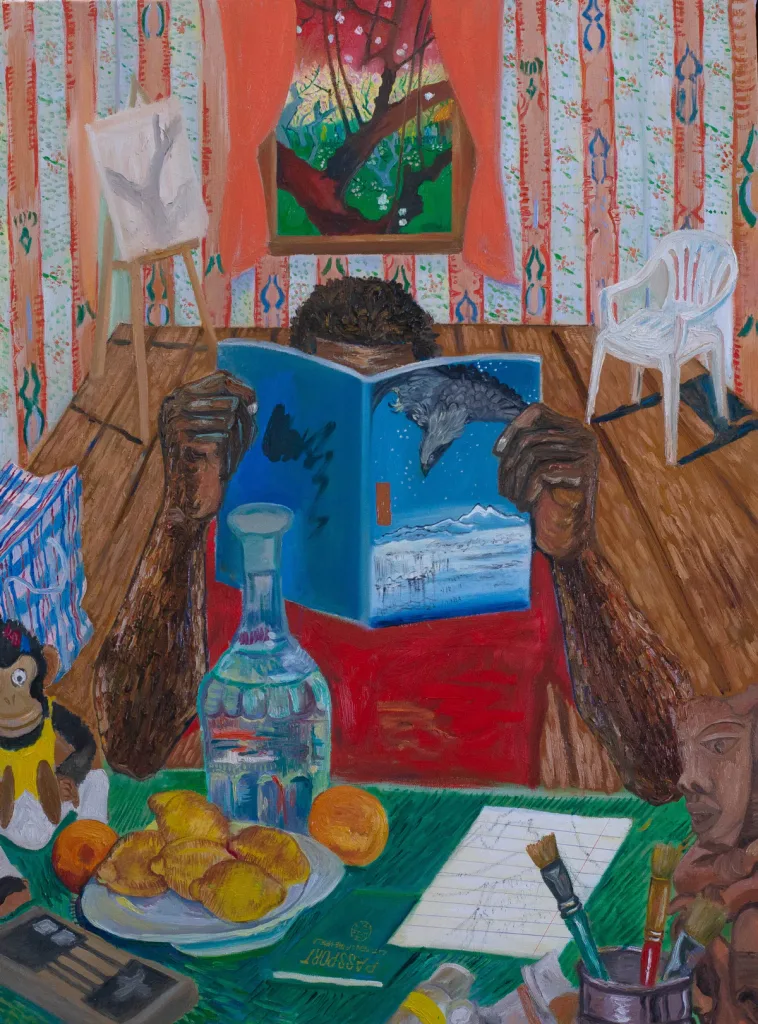

The future is already unfoldingand it is bold, expansive, and grounded in homegrown narratives. Projects like the Van Gogh x John Madu: Paint Your Path, showing at the Van Gogh Museum from the 30th of May to the 7th of September, 2025, reinterpret Vincent van Gogh’s visual language through West African perspectives. The exhibition serves as a bridge, illustrating how African artists are actively reshaping global art histories—not from the margins, but from the center. This landmark exhibition, the first of its kind by a contemporary African artist, signals a growing appetite for storytelling that transcends geography while remaining rooted in place.

Across the continent and diaspora, there is a groundswell of energy from all corners of the ecosystem—artists, curators, writers, collectors, and institutions alike.

“There is such energy and momentum from artists, new and established gallerists, emerging curators fresh from the institutions, new institutions, new residencies, art fairs, writers, and collectors,” notes Ed of the Ed Cross Fine Art. “It is a potent mix that will guarantee healthy growth in the sector.”

Growth, however, does not mean imitation. It means deepening what already exists, but on African terms.

“African art is no longer peripheral, it’s becoming central,” states Shamiela of the Eclectica Contemporary. “Market wise, it will continue gaining serious traction, with more artists entering blue-chip territory. Culturally, the narrative is increasingly being driven from within Africa: more homegrown infrastructure, more critical discourse, and more artists defining their own movements on their own terms.”

This cultural recalibration demands a shift in language as well. As Shamiela asserts, “We also need to stop framing ourselves in deficit terms.” She further highlights how South Africa, for instance, hosts two major fairs, FNB Art Joburg and Investec Cape Town Art Fair, both of which rival, and often exceed, the standards of international art fairs. In like manner, African museums, institutions, and artists are no longer supporting characters in the global conversation; they are authors of it.

Ultimately

The rise of African art as a global asset class cannot be measured by market demand alone. It must be understood through the lens of sovereignty; where value lies not only in scarcity or speculation, but in the ownership of narrative, infrastructure, and legacy.

For artists, collectors, investors, and cultural institutions, this signals a deeper shift: the next decade won’t just be defined by who is watching African art, but by who is writing it, preserving it, and shaping it from within. The future of African art is not emerging, it is self-authored, expansive, and already in motion.