Below are two exhibitions that have recently opened at WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery Cape Town.

Firstly, Dan Halter and WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery are pleased to present ‘Dust in the Balance’, Halter’s solo exhibition. This is an exploration of displacement and the colonial and post-colonial systems of expropriation and violence, however, these themes can only be understood in this current body of work when one considers Halter’s understanding of place. Throughout Halter’s work there is a distinct sense of belonging to a ‘home’, which is a location of mixed memory and materiality existing in a plural and liminal space between Zimbabwe, Switzerland and South Africa. His work is a construction of place, interrogating post-colonial life, as much as it is a site of painful memories and nostalgia.

Dan Halter has a biological connection to Switzerland through his parents’ Swiss roots, this has often been the invisible hand on the tiller of his art practice, but these roots have an arresting significance. Although nostalgia derives from the Greek words ‘nostos’ (home) and ‘algos’ (pain), it is a notion closely associated with the Swiss. The disease of Nostalgia was first observed and identified in 1688 by the Swiss doctor, Johannes Hoffer, amongst Swiss soldiers who had left their Alpine homeland. Hoffer diagnosed the disease as an affliction of the imagination. According to Hoffer, it created ‘an uncommon and ever-present idea of the recalled native land in the mind.’

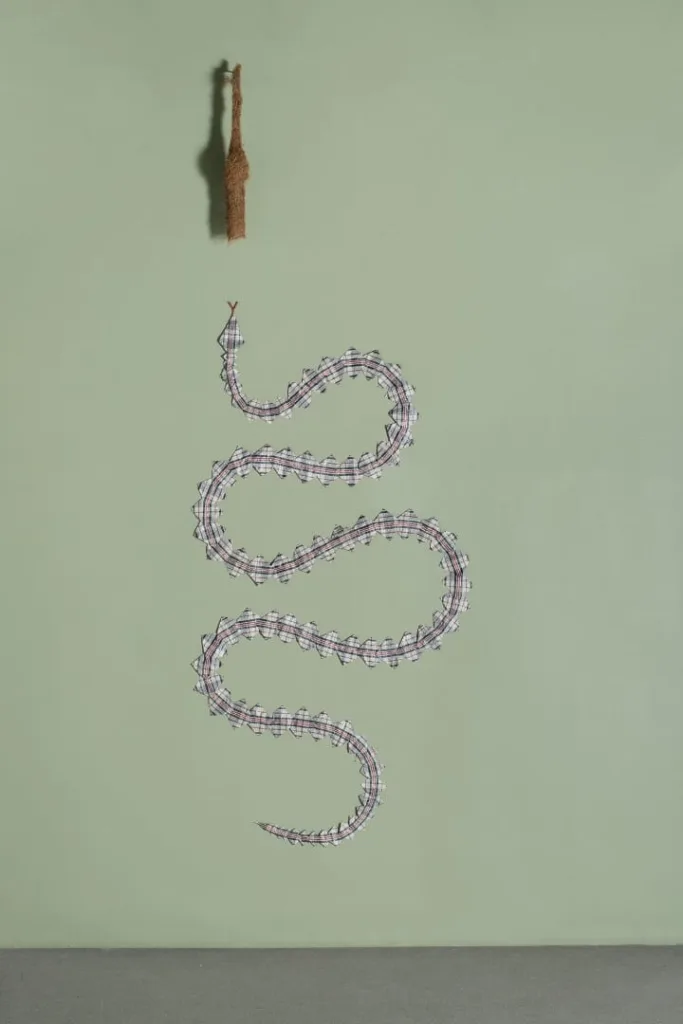

Halter, with his almost obsessive interest in materiality and cultural expression both African and Swiss, fills his work with material minutiae. Certain iconic images, the China bags of displaced migrants, texts relating to place, the African art of weaving, ID documents, money and the German ‘blaudruck’ material, all surface and resurface in his work. His artistic practice in many senses is an investigation of the effects of displacement. Nostalgia was, as Hoffer realised, brought on by displacement. Its cure, he discovered, was the act of returning home. What distinguishes Halter from the Swiss soldiers of the 17th century, who could make the journey home, is not only his critical engagement but the plurality of home for the colonial subject. Home is not simply a place of wonder and a source of recovery. In fact, the ‘home’ of the nostos is no longer a place, it is a fabrication of confused pluralities.

A recurrent theme in Halter’s work is one of the darkest moments of his life, the attack on his parents in their home in Harare in 2005. The plans and images of the house, designed and built by his grandfather in Harare, occur in the work ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past. (Blaudruck)’ 2022. The work is an abundant supply of dark references and meanings. The embroidered hand-made blaudruck fabric, with its industrial Germanic origins, contains within it the notion of a ‘blueprint’. The blueprints of the house appear in the pattern. But this is not simply a reflection on home, the ‘druck’ also contains a notion of violence, of push or ‘hold down’. And the force in the printing process of the fabric become manifested in the work. Violence or ‘druck’ is seemingly revealed in the pattern in what looks like the round bruising of skin. But this is not the only reference to that deeply personal moment. Zino irema rinosekerera warisingadeagain is Shona for ‘They smile but they don’t mean it’, a reference to the attack. The Zim dollars from the attack torn into the forms of broken teeth is an allusion to the trauma of that day. It is the insincere smile of 400 years of colonial contact, a smile that is pregnant with violence.

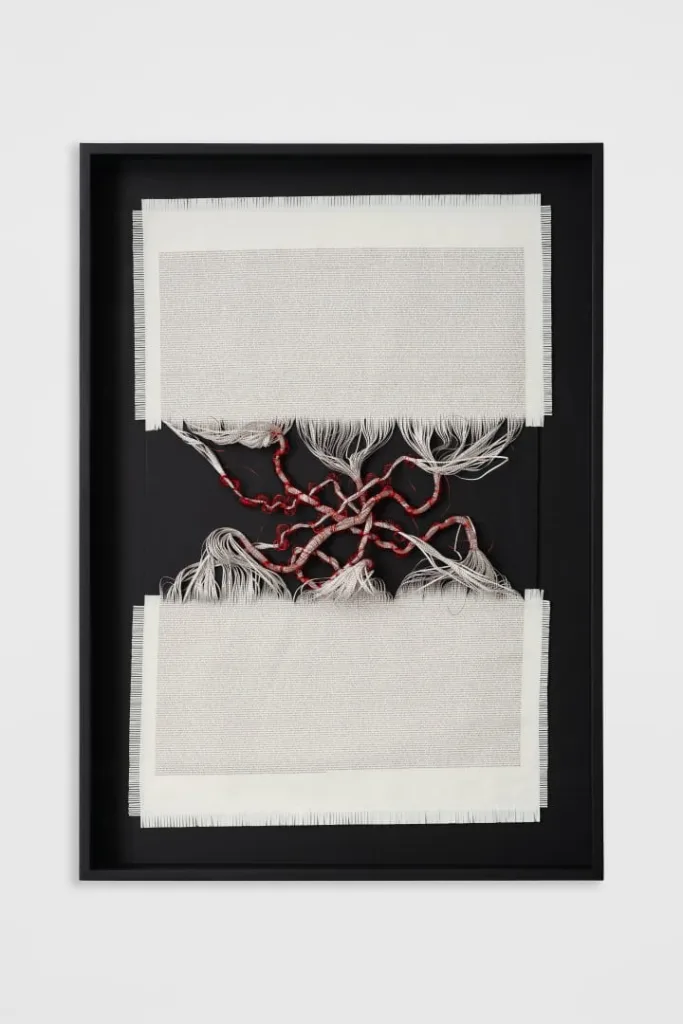

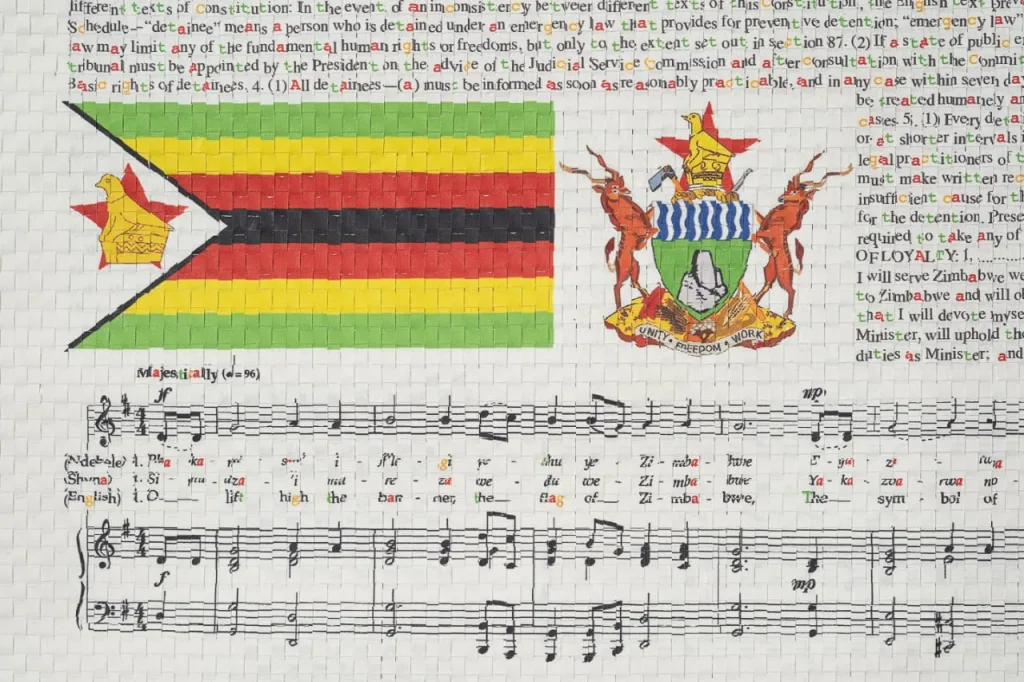

This specific crime is in many senses weighed up in ‘Dust in the Balance’ against all the other colonial crimes that have haunted Southern Africa. In many of the works, the colonialism and its aftermath are placed in the balance. In one such work, ‘On Trial for My Country’, the Zimbabwean novelist and historian Stanlake Samkange’s seminal novel of the same name is reproduced over the Zimbabwean flag, its cut ribbons lie in the balance of justice. Samkange’s novel places both Cecil John Rhodes and the Ndebele King, Lobengula, on trial and controversially allowed the reader to assess who was the criminal and who was the victim. In Halter’s work we quite often get the sense that victimhood is both complicated and confusing, although the crimes might be clear. In ‘When the missionaries came …’, the pronouncement is clearer but the conceit of weighing the crime is continued.

Dan Halter presents works of a world without clear values and borders, his feeling towards fabrication and construction arrive from the trauma and violence of the colonial and post-colonial contact. But there is another aspect to Halter’s work that elicits a story of creative collaboration. From the Blaudruck (and its similar African wax print process), in Stanlake Samkange’s work, and Halter’s engagement with weavers and wire artists there is a collaborative and generative practice. It is a practice that in some senses is the counter balance (or maybe the eponymous ‘dust in the balance’) to the dark forces that have surrounded much of the past 400 years of Southern African history. ‘Dust in the Balance’ opens on the 11th of December 2024 and will run until the 25th of January 2025 at WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery in Cape Town.

Secondly, WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery is pleased to present ‘Condescending’, a solo exhibition by South African based Namibian artist Tangeni Kambudu. ‘Condescending’ covers mirrors and why mirrors fascinate and unsettle us; we go to them to seek reassurance as to how we appear in the world. But there is more to the mirror than what, at first, meets the eye. There is the world around you: the room in which you find yourself, the objects that surround you, the people who sidle up to you or pass you by. This is what interests Tangeni Kambudu: what does a mirror reflect beyond the self? When we look in the mirror, what do we want to see, and how does that desire function as a preclusion? What are we unwilling–or perhaps unable–to see?

Reflection, transparency and preclusion are the three axes that form the matrix of Kambudu’s practice, using materials such as mirror, glass and muted colours could not be more fitting. While the artist has worked with glass and mirrors, this exhibition sees him experimenting for the first time with reflective vinyl. Due to the material being extremely sensitive and scratching or tearing easily, it requires precise handling on the maker’s part. Kambudu therefore works slowly and methodically: his emotions are controlled, and his movement is focused. Each cubicle is carefully etched by hand. Each glimpse of colour is delicately painted, often listening to classical music while he works, entering a meditative state. This disciplined manner of working highlights Kambudu’s respect for craftsmanship, which he says is losing purchase in a world that values efficiency above experti

Kambudu’s background in fashion design is visible in ‘Condescending’, it can be seen formally in the shapes he illustrates and then cuts to construct his pieces. In many ways, they resemble the patterns dressmakers use to construct garments. This effect is reinforced by the layers in which Kambudu works. Each frame contains two panels of glass or a mirror. One image is superimposed upon another, resulting in a palimpsest. The viewer’s reflection becomes lost or distorted in this web of fragmentation. But that is what mirrors do: distort the image. The image we access in the mirror is not our true self but a refraction–not a whole self, but a fragment thereof.

‘Condescending’ gives rise to reflection on this very issue. Do we condescend ourselves when we take the fragmentary image we see in the mirror for granted? Do we condescend others by passing judgment on the fragments we perceive in them? To answer these questions, it might be helpful to note that condescend is a word with an interesting etymology. Today, it has a negative association: to condescend is to make one feel inferior. Literally, however, the word means to climb (send) down (de) together (con). In the Middle Ages, it had a positive connotation: to condescend was to waive one’s privilege, to willingly assume an attitude of equality between fellow men. In this way, we might think of the mirror as an equaliser: it is impersonal; it does not flatter; it boasts no hierarchy. It merely questions the onlooker. What do you see? What don’t you see? Why? ‘Condescending’ opens on the 11th of December 2024 and will run until the 25th of January 2025.