In a controversial cultural development, two prominent British museums have agreed to return looted gold and silver artefacts to Ghana under a long-term loan arrangement.

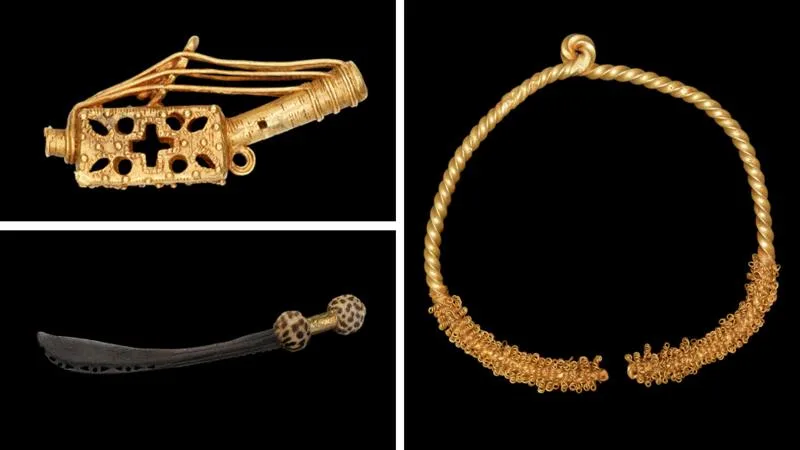

This involves the British Museum, and the Victoria & Albert Museum, in conjunction with the Manhyia Palace Museum in Ghana. This decision comes amidst mounting pressure on U.K. institutions to confront the legacy of colonialism and the acquisition of treasures during the era of the British Empire. The loan agreement, comprising 17 items, including 13 pieces of Asante royal regalia acquired by the V&A at auction in 1874, marks a pivotal moment in the restitution of cultural heritage.

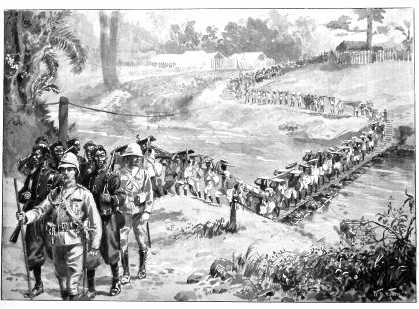

During the Anglo-Asante wars of 1873-74 and 1895-96, British troops actively looted these artefacts, marking a painful chapter in Ghana’s history. These treasures hold immense cultural, historical, and spiritual significance to the Asante people, serving as tangible links to their past and colonial experiences.

Amid a global reassessment of colonialism, several countries, including Nigeria, Egypt, and Greece, alongside indigenous communities worldwide, have demanded the repatriation of looted artefacts and human remains. Recent agreements between Nigeria and Germany, as well as France’s return of artworks to Benin, underscore a growing momentum toward restitution.

However, the U.K.’s response has been more measured, citing legal acquisitions and the preservation efforts of institutions like the British Museum. The government emphasized that the loan agreement with Ghana does not set a precedent for the contentious Parthenon Marbles, subject to a prolonged diplomatic dispute with Greece.

Max Blain, the Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s spokesperson, stated that Britain had previously lent items between museums and expects the museums to return the items at the end of the loan period.

The artefacts covered by the agreement include a diverse array of items, such as a “soul disk,” a peace pipe, and sheet-gold ornaments. While representing only a fraction of the Asante objects held by British museums and private collectors globally, their return symbolizes a step towards reconciliation and justice.

Nana Oforiatta Ayim, special adviser to Ghana’s culture minister, hailed the agreement as a “starting point” in addressing historical injustices. She emphasized the ultimate goal of returning the regalia to its rightful owners, comparing the loan to borrowing items stolen from one’s home.

The decision has further sparked controversy and elicited mixed reactions, with many questioning the ethical implications of loaning items acquired through theft. This move prompts a deeper reflection on the history of stolen African artefacts by the British people, a legacy that continues to resonate in discussions of cultural heritage and restitution.