MoMA’s “New Photography” series triumphantly returns, shedding conceptual haze and delivering a vibrant, captivating exhibition. This time, the focus is on the Nigerian city of Lagos, offering a unique geographic perspective rarely explored by MoMA. By dedicating the show exclusively to photographers with ties to Lagos, curator Oluremi C. Onabanjo challenges conventional notions of documenting a city and its inhabitants through photography. The result is a deeply immersive experience that pays homage to Lagos’s rich history and diverse citizenry while exploring the multifaceted nature of the medium itself.

30 x 42 cm

With a smaller selection of just seven artists, compared to previous editions, Onabanjo allows for a more profound exploration of each photographer’s practice. One standout artist, Logo Oluwamuyiwa, captures the essence of Lagos through his unconventional and mesmerizing lens. His photographs often distort reality with oblique angles, offering a fresh perspective on the city. In “Oil Wonders II,” Oluwamuyiwa presents an upside-down shot of two individuals, their upper halves reflected in a puddle below. Through an array of prints, vinyl wallpapers, and films, he consistently reorients our perception of Lagos, unveiling hidden dimensions.

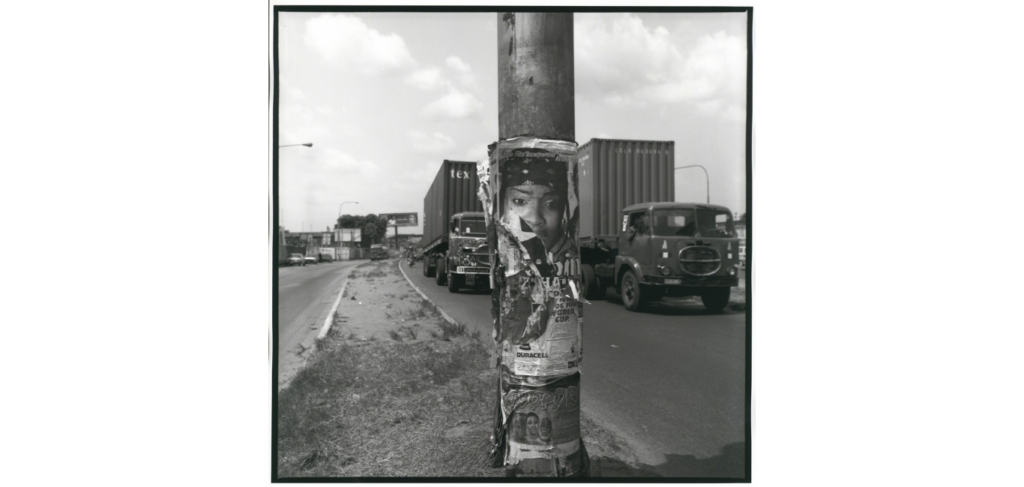

Akinbode Akinbiyi, another featured artist, takes us back in time with his serene black-and-white photographs of Bar Beach, a once-beloved seaside destination. Akinbiyi’s works provide a glimpse into a bygone era, capturing moments of leisure and tranquility. The series, aptly named “Sea Never Dry,” evokes a dreamlike quality while subtly hinting at the forces of history that shaped the city and its inhabitants.

In contrast, Amanda Iheme’s photographs appear as archival documentation, preserving the vanishing history of Lagos. These images seemingly depict ordinary objects, such as cassette tapes and transit tickets, yet they symbolize the erasure of cultural heritage. One poignant photograph showcases Casa de Fernandez, a 19th-century structure demolished shortly after Iheme captured it. Through her lens, Iheme becomes a witness to the ephemeral nature of the past, solidifying its existence in the face of destruction.

Abraham Oghobase, with his installation “Constructed Realities,” explores the fragility of history and the lingering impact of colonialism. Utilizing silk imprinted with British texts from the past, Oghobase superimposes re-photographed colonial images, creating a haunting juxtaposition. As portions of the photographs fade away, the subjects become ghostly remnants, leaving behind a sense of loss and disconnection.

Karl Ohiri’s contribution to the exhibition centers around his Lagos Studios Archives project, wherein he collects damaged studio portraits and breathes new life into them. These re-photographed images bear the marks of time, displaying vivid bruise-like splotches and altered hues. Ohiri’s works possess a mesmerizing beauty, capturing the haunting essence of history and memory.

While Yagazie Emezi’s documentary photography presents a more conventional approach, her powerful images of protests against police brutality during the #EndSARS movement of 2020 resonate deeply. Emezi’s photographs transport viewers to the streets, capturing the strength and resilience of those fighting for justice.

182.9 × 142.2 cm

Beyond documenting Lagos’s physical roads, these photographers provide less obvious pathways to the heart and soul of Nigeria. Their works invite viewers to explore the complexities of a nation and its people, ultimately encouraging a broader understanding of faraway places.

Oluwamuyiwa’s photograph “Lagos Hosts” encapsulates this sentiment, featuring the backside of a weathered bus with a sign proclaiming “LAG