In traditional Igbo society, Mbari houses functioned as crucial’ retreat camps’, offering individuals a sacred space to appease the gods. Dedicated to deities overseeing time, balance, and the earth, including Ala, the earth goddess, the Mbari house acted as a holy sanctuary. Within these sacred spaces, sculptures depicted animals, blended human-animal figures, and scenes from everyday life. They served as profound symbols conveying core African values, such as hard work and integrity.

The Igbo people, constituting over 60% of the Southeast Nigeria population and encompassing communities like the Anioma people, Arochukwu, and Ontisha territories, have a rich cultural history. Spiritual worship, particularly the veneration of deities, was prevalent in Igbo land. Mbari houses were pivotal in stimulating intellectual curiosity, allowing people to derive spiritual and conscious meanings from various contexts.

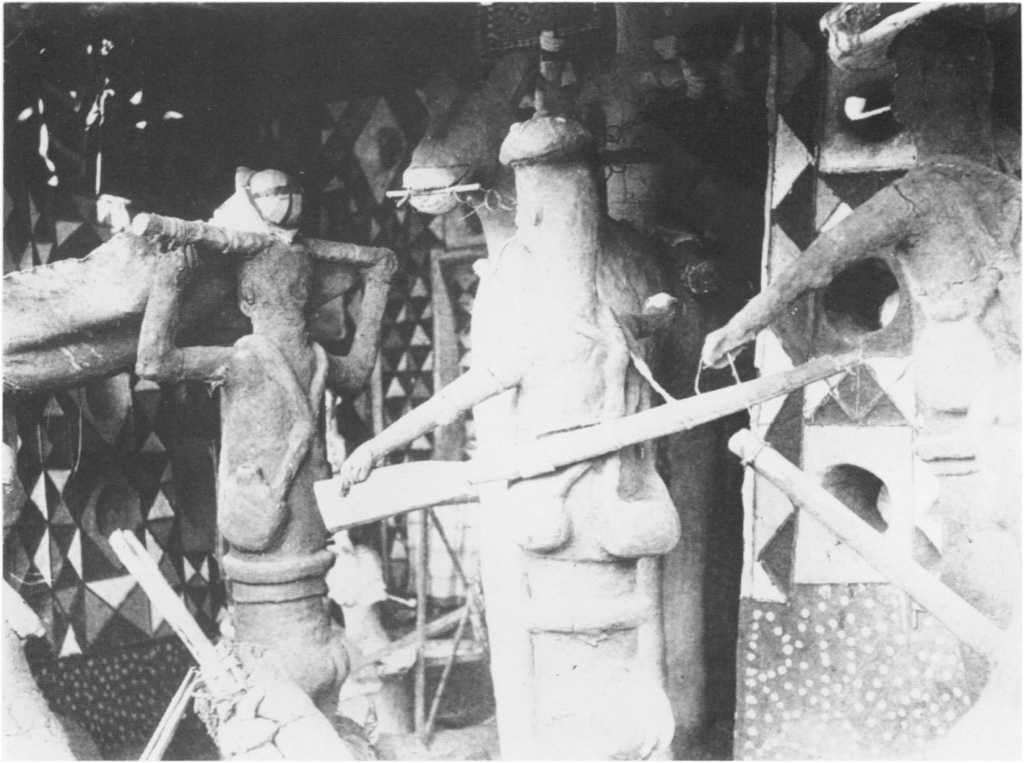

During colonial rule, Mbari sculptures actively portrayed diverse figures, explicitly reflecting the influence of the UK as the colonial power in Nigeria. The 1930s marked a transformative era for Mbari houses, influenced by the stability and prosperity of the Pax Brittanica in Owerri (Igbo land). Traditionally, builders used local materials like sun-dried clay, organic substances, and tints, reflecting the transient nature of Mbari houses. These materials also symbolized the ‘renewal’ of the earth in harmony with the changing year.

Building Mbari houses was not just a physical endeavor but a spiritual journey for builders and community members. The process involved rituals and the avoidance of certain pleasures, signifying a period of significant spiritual transformation to appease the gods. Local communities visited the sacred place, featuring over 200 sculptures that symbolized the ‘cleanliness’ of the body and soul for optimal well-being.

Amidst acculturation in the 1930s, Mbari houses integrated new and familiar elements, reflecting the evolving world context. Sculptures dramatized British colonial powers, using secular representations to convey spiritual concerns. They gazed outward to a changing world of ideas, products, local events, and the values and vices of colonialism. Catechists, white men, World War I, and motorcycles became symbolic representations of foreign elements in traditional Igbo society.

Over time, the pros and cons of acculturation influenced the fate of Mbari houses as modern religions, namely Christianity and Islam, gained prominence. This transition marked a shift from vibrant cultural expressions to historical artifacts. Nevertheless, they served as a visual testament to Igbo ancestors, offering insights into the changes during the colonial era.