In the past 90 days, 97 women (and counting) have lost their lives to gender-based violence in Kenya, equating to at least one woman killed every day over the last three months. These alarming statistics are not unprecedented. Earlier this year, a nationwide march was held in response to the ongoing gender-based killings. While the reasons behind the surge in violence remain unclear, Kenyan contemporary artists have taken it upon themselves to address this pressing issue through their art.

The hashtag #endfemicideke, coined by artist Peterson Kamwathi, sparked an outcry among Kenyan contemporary artists, inspiring them to create works that celebrate African femininity in all its complexity. The portrayal of femininity and the representation of women are crucial to societal progress. In Henk Van der Laan’s book, In an African Direction: A Search for a Mind of One’s Own in a Global Village, he argues that while Western depictions of symbolic female figures—like Mary, the mother of Christ, or the goddess Isis in ancient Greece—aspired to represent higher ideals, they often came at the cost of real women’s rights. In ancient Greece, for instance, women were excluded from property ownership and denied recognition despite their idealized portrayals. The recent exhibition at Fondation Carmignac, titled The Infinite Woman, delves into these paradoxes by exploring how Western representations of women have shaped their current realities.

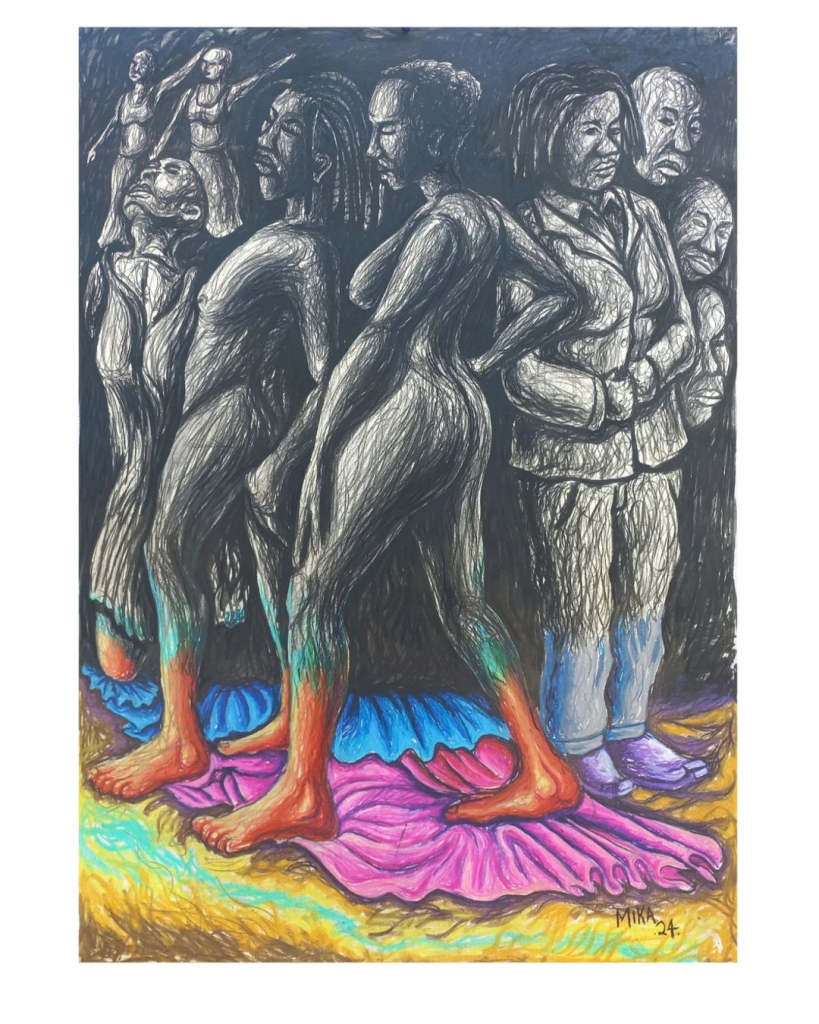

Medium: Charcoal and soft pastel on paper

Size: 107cm×77cm. Image courtesy of artist’s Instagram.

In Kenya, the recently concluded Nairobi Affordable Art Show featured female artists as exhibitors and subjects. Contemporary artists, galleries, and collectives continue to tackle these issues head-on. Through their work, they confront pressing social problems like toxic masculinity, unresolved trauma, and the enduring impact of colonial systems on societal roles and perceptions of women.

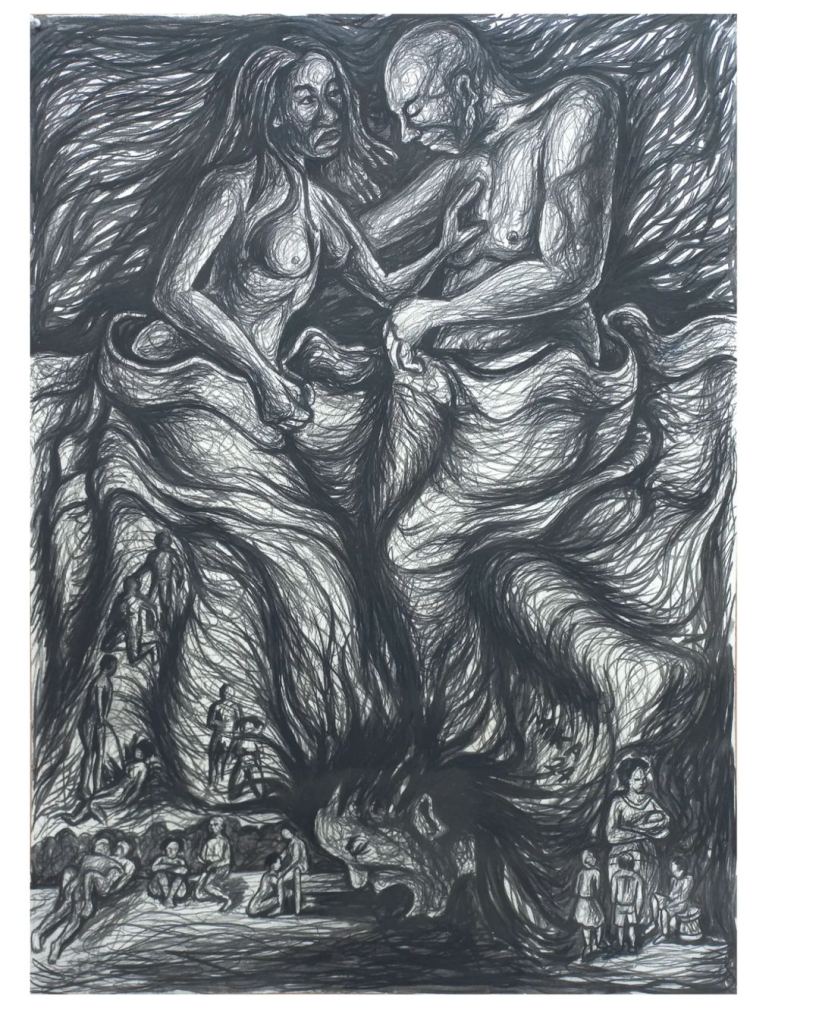

During a walk-through of Mika Obanda’s The Commentary exhibition at Wajukuu Arts Collective, it became clear that this showcase was, as its title suggests, a commentary on the issue of gender-based killings in Kenya. Through large works in charcoal, Obanda explores the origins, impacts, and deep societal damage caused by gender-based violence across communities. Curated by Ndungu Kimani and Mbirua Nyambura, the exhibition is set in Lunga Lunga slums, where Obanda was born and raised. It boldly addresses themes such as the #usikimye (do not stay quiet) movement, religion-imposed gender roles, unaddressed trauma, the rights and stigmatization of sex workers, and the cultural stigma surrounding victims of gender-based violence.

Featuring 13 large works in charcoal and pastel, Obanda draws from personal experiences. “I had to reconnect with my roots and understand myself,” he shared during our exhibition walk-through. “I needed to deeply connect with the work, delving into my identity and the realities I’ve witnessed in my home and community.”

A recurring motif in his artwork is the depiction of large crowds in the foreground or background, symbolizing either “victims” or “perpetrators” of gender-based violence. The inclusion of diverse figures, especially children, serves as a powerful symbol of the alarming “induction of a new gender-based violence culture” that seems to be taking root in Kenya in 2024.

Obanda’s approach is meticulous, portraying real-life scenarios with unflinching honesty. In works like History of The Sheets, he directly confronts the challenges faced by women in sex work—one of the oldest professions—highlighting the lack of human rights protections and the dangers they endure.

Additionally, he critically examines the influence of religion in shaping gender roles, particularly regarding authority. Religious interpretations that align with the church, Jesus Christ, and the husband have reinforced male dominance within families. This hierarchical structure, he argues, is a significant factor contributing to the continued violence against women today.

Another noteworthy exhibition is Michael Soi’s Sex and the City, which challenges the societal stigma surrounding sex and sex work by depicting various individuals, often respected members of the community, who engage in the nightlife scene. These exhibitions invite viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about societal hypocrisy and gender dynamics.

Visiting these exhibitions left me conflicted. Admittedly, growing up in a religious household that criticized nudity and sexual immorality I often see these topics through a narrow lens. Walking through these exhibitions has forced me to question my belief in the treatment of women, prompting me to reflect on the experiences of others and the tragic reasons why so many relationships end in violence, particularly against women.

As a 25-year-old, I know at least 6 out of 10 women in my circle of friends and family who have been victims of gender-based violence. This is a tragic reality, reflecting systemic issues in the perception of home and family values in Kenya.

In response to this national crisis, Kenya will once again hold a nationwide march against gender-based violence on December 10, 2024. This march aims to amplify voices calling for an end to gender-based violence and to push for meaningful change. By uniting together, the country continues to confront this epidemic, emphasizing that the fight against femicide remains a priority and that silence is no longer an option. Ongoing dialogues and advocacy are essential in driving the change needed to protect women’s lives