Julien Benoit, an associate professor at the University of Witwatersrand recently published a journal. In the journal, he hypothesised that one of the creatures in a South African cave art (“Horned Serpent” panel) could be a dicynodont.

The “Horned Serpent” panel is 1.2m long, 5m thick and made of Molteno Sandstone. In its entirety, it portrays depictions of warriors and other recognisable modern African animals. However, one particular creature stands out in the scenery. Its features largely coincide with those of the dicynodont. The animal went into extinction over 200 million years ago and even pre-dates the existence of dinosaurs.

Richard Owen described the dicynodont in his 1845 “Report on the Reptilian Fossils of South Africa.” That was the first formal scientific description of the dicynodont. Or so it seemed.

With the emergence of this newfound possibility, the history of the creature’s scientific discovery might have just changed. Benoit utilises ethnographic, archaeological and palaeontological evidence to determine the time the painting was created and how the creature in the panel is the dicynodont. From his research, this San rock art is dated between 1821 and 1835. It could even be older. Consequently, it is at least ten years older than Richard Owen’s discovery and description.

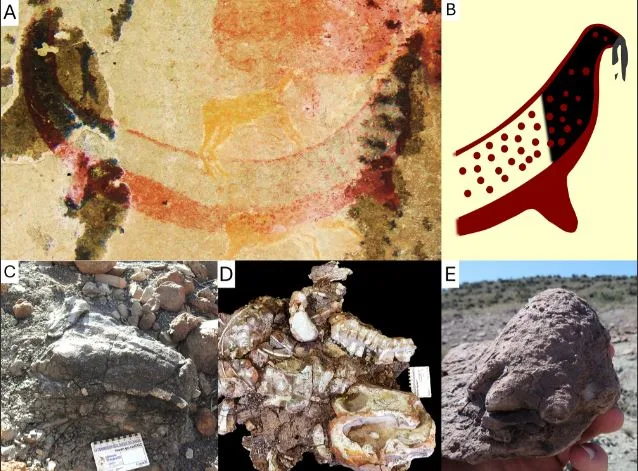

The “Horned Serpent” Panel is situated at La Belle France in Free State Province, South Africa. It was created by the San people whose paintings are generally inspired by their surroundings. With the inclusion of other elements, the painting depicts a spotted, tusked animal with a very curved back which may be an “opisthotonic death pose” and very short limbs. The most distinct feature of this painting is the downward orientation of the creature’s tusks. This is nothing like the curve of modern African animals. However, it is the exact orientation of the dicynodont’s tusks.

According to Benoit, there are a number of reasons why the South African cave art could be the depiction of a dicynodont besides the tusk orientation. While it is not out of the ordinary to find spotted creatures in San rock art, the spots on the creature are consistent with the wart-like skin found on some dicynodont fossils in that area.

A: Photo of the tusked animal of the Horned Serpent panel. B: Interpretive drawing of its head. C: Skull of a Lystrosaurus (14-03-2024, Oviston Nature Reserve) showing the prominent tusks, photographed in situ at the moment of its discovery, before excavation, and unprepared. D: Complete skeleton of a Lystrosaurus (BP/1/9100, Oviston Nature Reserve) with its vertebral column curved into an opisthotonic “death pose”, ex situ, prepared. E: The ‘mummified’ foot of a Lystrosaurus (28-08-2022, Fairydale, Bethulie District) showing the warty aspect of its preserved skin, ex situ, unprepared. (Image and detailed caption courtesy : Julien Benoit)

Apparently, the San people were in the habit of drawing inspiration for their art from their surroundings. Benoit asserts that they did not rely on pure imagination to conjure up figures in their rock art. Hence, it is not much of a leap to infer that the mysterious creature in the “Horned Serpent” panel was also inspired by something tangible around them.

The La Belle France area in the Karoo Basin has an ample supply of fossils that are still intact. Dicynodont fossils are just one of the many kinds of fossils there. Therefore, it is very likely that the San people came across fossils of the dicynodont. It is even more likely that they interacted with them enough to tell that they were the remains of creatures that once existed.

This suggests indigenous palaeontology (the study of fossil animals and plants) and the likelihood of a geomyth about dicynodonts. Benoit further states that even if the painting of the tusked animal had a purely spiritual meaning, the hypothesis is still valid. It could have been imagined with the dicynodont fossils in mind.

Altogether, this new line of reasoning is a welcome insight into the possible motivations of some African art. It also discourages the idea that the West introduced all things scientific to Africa. Our ancestors’ methods may not have been the westerner’s definition of refinement. However, they were effective and driven by intelligence.