Efie Gallery has just opened its latest exhibition, Time Heals, Just Not Quick Enough, curated by Ose Ekore. Framing time as a partner in the process of becoming, Ose spoke with ANA on curating contemporary African art and the creation of “Time heals, Just Not Quick Enough”. Moreover, he shared insights on his project Bootleg Griot, and his personal experiences as a Nigerian cultural worker in the UAE.

R.M: What principles or ideas form the foundation of your curatorial practice?

O.E: My curatorial practice is rooted in curiosity. I’m deeply interested in exploring the artistic practices that emerge from the African continent and its diaspora. As I continue to learn, I see my role as a curator as one of creating conditions where these works can be encountered with care. This involves being intentional with language, framing, and the way space is held. It also requires resisting the urge to over-explain or overly simplify—allowing the works to speak on their own terms.

R.M: How do you view the role of contextual alignment as a method of archiving African and diaspora narratives?

O.E: I see contextual alignment as a deeply generative way of archiving African and diaspora narratives—one that prioritizes resonance over categorization. It allows connections to emerge across time, geography, and medium without flattening difference. In my practice, contextual alignment isn’t about forcing coherence but about leaving room for multiple truths to exist side by side. I think this approach resists extractive frameworks and instead centers relationality, care, and the lived experience embedded in the work.

R.M: In today’s dynamic global landscape, what does it mean to be a cultural worker?

O.E: For me, being a cultural worker is about listening closely: to artists, to audiences, to the silences between things, and allowing meaning to emerge slowly, on its own terms. The role implies a constant negotiation—with systems, with histories, with responsibilities. It means tending to stories that might otherwise be overlooked, misrepresented, or lost. And doing so with care, context, and mindfulness. In a global landscape shaped by rapid circulation and uneven access, the work questions how culture moves, who it serves, and what it makes possible.

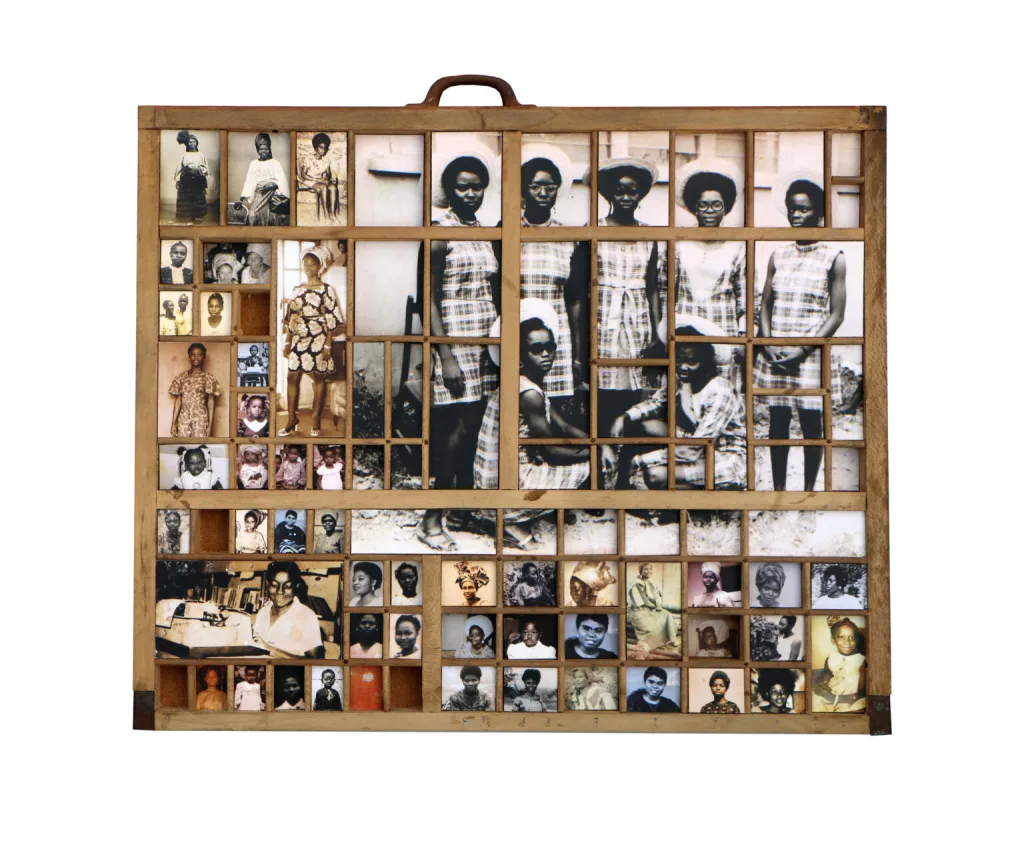

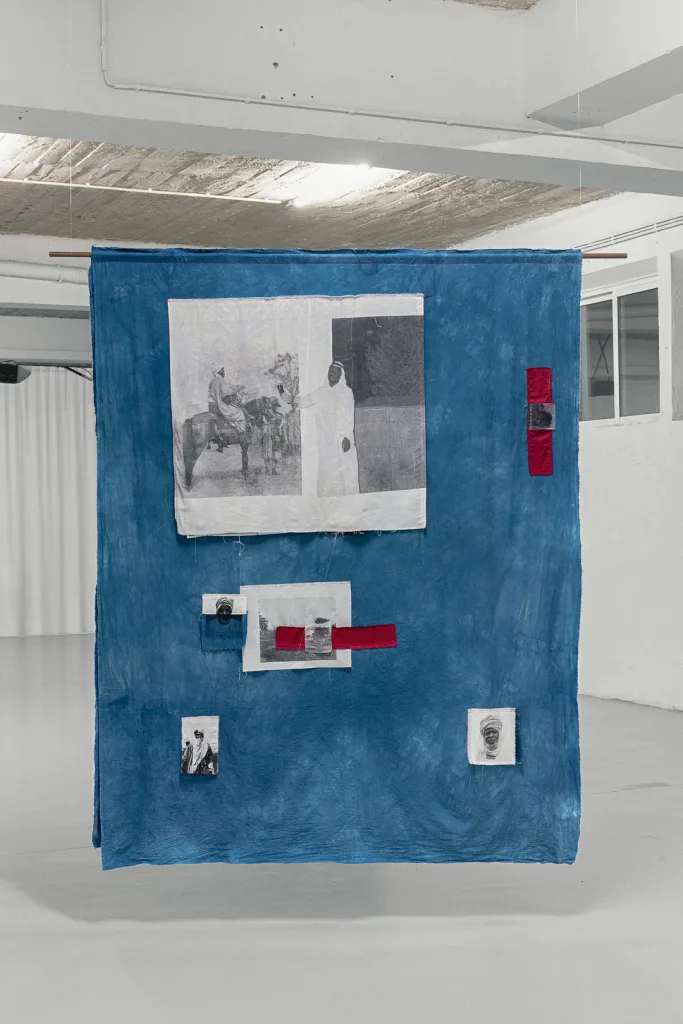

R.M: What does the cultural preservation of photographic media mean to you?

O.E: I think it’s a practice of honoring the lives, contexts, and memories they hold. Photographs are not neutral; they carry the weight of who took them, why, and under what conditions they were circulated or archived. Preserving them means reckoning with their layered meanings, their silences, and sometimes their absences. Within African and diaspora contexts, it also becomes a form of resistance. It resists erasure, imposed narratives, and the idea that our histories are only valuable when legible to others. Cultural preservation, then, is not only about keeping photographs intact—it’s about making space for them to be re-read, re-framed, and re-activated across generations.

R.M: Can you tell us about Bootleg Griot and its significance?

O.E: Bootleg Griot is a public library project I co-founded focused on experimental modes of cultural preservation. Rooted in the figure of the griot—the West African oral historian—we’re interested in how narratives travel, mutate, and survive outside institutional frameworks. The term bootleg speaks to informality, circulation, and resistance. It values what people pass hand to hand, whisper, remix, or leave undocumented. Through a thoughtfully curated collection of conversations, and interventions, Bootleg Griot creates a space that holds memory in multiple, shifting forms, where different fragments are embodied and improvised. It’s significant to me because it blurs the line between archiving and creating, between listening and voicing. It challenges the idea that institutions must preserve history in rigid, formal ways to make it seem legitimate.

R.M: How does Bootleg Griot ensure that information—such as photographic records, books, films, and ancient relics—is accessible to African creatives in the UAE?

O.E: Access is at the core of our ethos at Bootleg Griot. This is not just access to materials like books, films, or photographic records, but access to context, interpretation, and resonance. For African creatives in the UAE, Bootleg Griot functions as an informal, relational archive. It circulates knowledge through conversation, listening sessions, shared libraries, and ephemeral gatherings. It’s about creating networks of trust and exchange, where knowledge can live, move, and grow organically.

R.M: What is the current program at Efie Gallery about, and what themes does it explore?

O.E: Rather than presenting time as a fixed or neutral backdrop, the exhibition approaches it as an active, volatile force–one that disrupts, lingers, accumulates, and resists closure. Time emerges not only as subject but as method. Through layered archival material, invoked through personal and collective histories, and embedded in acts of refusal and repetition. Collectively, the works do not offer a unified timeline. Instead, they come together to present a constellation of temporality–some fragmented, some cyclical, others suspended or speculative.

R.M: What does the title Time Heals, Just Not Quick Enough… mean to you personally or curatorially?

O.E: time heals, just not quick enough… is a meditation on time’s rhythms, its ruptures, and its capacity for transformation. It’s an invitation to reconsider the moments we rush to and through, the silences we overlook, the histories we inherit, and the futures we dare to imagine. In embracing slowness, repetition, and ambiguity, the phrase is a reminder that healing and understanding rarely arrive on schedule. But if we pause–if we learn to wait–we may come to see time not as something to overcome, but as a companion in the ongoing work of becoming.

R.M: What has your experience been like working with artists from Africa and the diaspora?

O.E: It’s truly exciting. Each person brings a unique perspective and practice. This opens up rich opportunities to discover fascinating connections—whether artistic, cultural, or historical. Honestly, I feel like a kid in a candy store.

R.M: What has stood out to you about living in the UAE? In particular, how has it shaped your experience with cultural integration, assimilation, and respect for diverse cultural identities?

O.E: Living in the UAE has been a complex and enriching experience. It has truly enriuched my understanding of cultural integration and respect for diversity. The country is a vibrant crossroads where many cultures coexist, which offers incredible opportunities for dialogue and exchange. What stands out is the delicate balance between assimilation and maintaining one’s distinct cultural identity. There is both space to celebrate difference and subtle pressures to adapt. For me, it’s about navigating these tensions with care and openness. I recognize that cultural respect is less about coexistence, but about actively valuing the histories, languages, and expressions that each community brings to the table. This ongoing negotiation shapes my understanding of how cultural work can meaningfully engage and reflect the multiplicity of identities here.

R.M: How important is it to develop new methods of sharing and preserving African oral Traditions?

O.E: Developing new methods to share and preserve African oral traditions presents a powerful opportunity to construct new narratives around African art and history. These traditions are dynamic and adaptable. By embracing new approaches, we can challenge dominant historical frameworks and create spaces where alternative, often marginalized, stories can emerge. This process allows us to rethink how we present African histories and artistic practices. It allows us to move beyond static archives, to living narratives ,that reflect the complexity, diversity, and creativity of African experiences today.