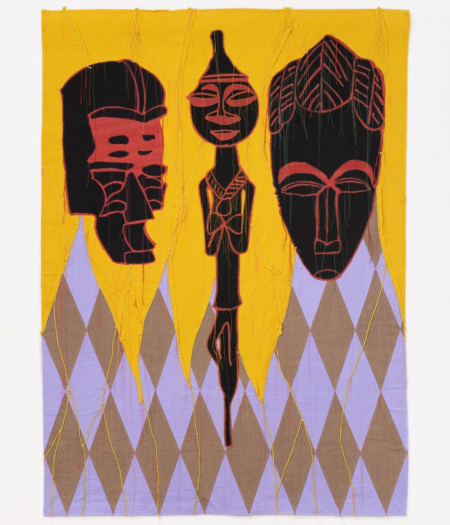

James Cohan Gallery in NY currently features an exhibition titled “Boomerang: Returning to African Abstraction” by Yinka Shonibare. The artist uses Dutch wax fabrics and the Nigil Mask to bridge the connection between Africa, its diaspora, and Western colonies. Shonibare’s new series, Abstract Spiritual, presents pictorial quilts that stretch and frame African artworks referenced by European modernist artists, emphasizing the foundational role of African and African Diasporic art in Western-European abstraction. The exhibition highlights the impact of African influences on notable artworks, including Picasso’s Harlequin paintings.

In his statement, he writes.

“In Boomerang I am conveying the origins of abstraction in African artifacts and the pivotal role [African artists] played in the development of Western modernist abstraction. My motivation is to acknowledge the contribution of African abstraction to the global language of modernist abstraction.”

R. M: What does African abstraction mean to you?

Y.S: In my upcoming exhibition, Boomerang: Returning to African Abstraction at James Cohan Gallery, I am conveying the origins of abstraction in African artifacts and the pivotal role African artists played in developing Western modernist abstraction. My motivation is to acknowledge the contribution of African conception to the global language of modernist abstraction.

R.M: As an African artist, your use of batik cloth invites personal connections; could you elaborate on its significance?

Y.S: I frequently describe myself as a ‘postcolonial hybrid,’ I often work with the brightly colored ‘African’ batik fabric, which I believe serves as a metaphor for migration. This material can be Dutch, Indonesian, and African simultaneously. The fabrics symbolize cross-cultural connections – I use this to explore the complex relationship between Africa and Europe, particularly the complexities of contemporary hyphenated identities.

R.M: What is your favorite artwork ( other artists included ), and why?

Y.S: I created Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle in 2010 for the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, London. It was the first commission by a black British artist and the first to reflect on its setting. The work is a scaled-down replica of HMS Victory, Lord Nelson’s flagship in the Battle of Trafalgar. For the ship’s large sails, I used colorful batik-patterned textiles. This fabric is a metaphor for the movement of people and global relationships. The work considers the legacy of British colonialism and its expansion in trade. I also love Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project, which I saw at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2004.

R.M: What has been your inspiration throughout the years?

Y.S: I have a passion for creating works that challenge ideas of authenticity. Throughout my practice, I use citations of Western art history and literature to explore the legacy of colonialism and empire within contemporary globalization experiences. I’m examining race, class, migration, and the construction of cultural identity. My works comment on the tangled interrelationship between Africa and Europe and their respective economic and political histories.

R.M: In traditional African culture, art is connected with the spirit world. What message or experience do you hope your African audience will take away from the upcoming exhibition?

Y.S: I want African audiences to engage with and enjoy the work like anyone else. African audiences are very plugged into the rest of the world and have a global perspective. I don’t expect their reception of the work to differ from anyone else’s.

R.M: Can African states protect cultural heritage through global involvement?

Y.S: I believe the arts should be independent of the states. Furthermore, I often prefer that skills are separate from government, as the state often does not lead to the best art.

R.M: The importance of inclusion and diversity is widely recognized in today’s art world. What advice would you offer young African artists regarding their role in promoting these values in art spaces?

Y.S: My practice deeply aligns with cultural exchange. Now, more than ever, we need to hear the voices of young artists, especially those whose identities have been overlooked for so long. The opportunity for artists to have the space and freedom to experiment and collaborate is a necessity. For this reason, I opened GAS – Guest Artists Space Foundation in Lagos, Nigeria. We have created a space where the artists can live and work. We also have a 54-acre farm and farmhouse outside of Lagos, which also hosts residents. We’re doing agriculture, sustainable farming, and a bit of conservation. We want to bring artists worldwide to Africa; I’m passionate about this work.

R.M: What advice would you give your younger self on maintaining cultural roots while navigating the international art scene?

Y.S: Be true to your origins to retain your African roots while participating in a global conversation.

The exhibition is on at James Cohan Gallery till December 2023. Be sure to check out this exhibition as we understand African abstraction’s contributions to contemporary and modern art today.