British-Ghanaian curator and author Osei Bonsu works out of Paris and London. His current position at Tate Modern as curator of international art entails organizing shows, expanding the museum’s collection, and increasing the representation of artists from Africa and the African diaspora. Bonsu has advised worldwide museums, art fairs, and private collections in his capacity as a preeminent curator of contemporary art. Through his online platform, Creative Africa Network, he has also mentored up-and-coming artists. As a contributing editor for Frieze magazine, Bonsu has also written for other exhibition catalogues and magazines covering the arts, such as ArtReview, Numero Art, and Vogue.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

AS: What inspired you to birth Africa Art now?

OB: African Art Now is a book that looks at 50 outstanding practices. Practices of artists both based on the continent and in the diaspora. The reason the book felt like a very important opportunity, really, was because there were so few books dedicated to what I view to be the kind of emerging generation of African artists. When I say emerging, I mean, their work hasn’t necessarily been given the attention, both critical and art historically, that it deserves in many cases. Thinking about a book that would bring together 50 extraordinary practices was the kind of opportunity to think of the breadth of creative practice across the continent and beyond. Also think about the ways in which artists are addressing very contemporary questions and issues through their work. The idea of African Art Now as a book was to think about the kind of trajectory of art books that would help inform a new generation of artists. Additionally, inspire other artists and young people to take up art. I was thinking specifically about people who’d maybe never visited an art fair or a museum, as well as those who would be considered industry insiders that have a great deal of knowledge and expertise when it comes to this area and trying to create a book that would be as accessible as possible. To be engaging in terms of its imagery and kind of breadth of, you could say, artistic expression, and to really allow the book to sign post.

AS: What are some of the kind of key themes and ideas that artists are addressing?

OB: One of the themes I wanted to address is that of family portraiture and how this kind of role of social portraiture that’s played such an important role within the Independence era is still being looked at by many contemporary painters. Who are using the portrait to explore this kind of dynamic of self representation and what that means within a wider frame. Particularly in the era of selfie culture and digital, you could say representation being the primary way that we communicate with one another. Another theme I wanted to address was that of postcolonial dystopias and artists looking at the kind of discontents maybe of how you could say kind of after the post colonial era. Then finally I look at the question of future ecologies, which addresses specifically the idea of climate change and this idea that beyond looking at reuse and recycling, which are these very simplistic ways, you could say that artists work with materials.

AS: I really relate and appreciate somebody putting the people that are trying their best to be out there doing it. What would you say for the “novices” that want to read the book? What do you hope would resonate with them?

OB: The book opens with the Foreword by rugby player, Maro Itoje. Part of the reason why I wanted Maro to be part of the book, not only because he’s a friend, but because he represents a generation of young people who, of course, have access to social media and are looking at art often through the prism of Instagram and Facebook and other social media platforms. I wanted to be cognizant of the fact that most people actually engage with art more in those ways than they do through traditional galleries or museum models. I think what Maro talks about in the Foreword, is growing up in a British-Nigerian household and how that shaped his understanding of this kind of deep visual culture that many of us are aware of when we grew up in an African household, be it through music, literature, textiles, all of these symbols of our cultural heritage are very present growing up.

AS: I feel like that is very relatable. That’s something that’s talked about now, independence. Most Africans, even if you’re home or abroad, you understand the feeling of independence. What was the process of creating this book, and what meaningful, memorable experience did you have while compiling it?

OB: I started the book with a list of the artists who I thought would be the most dynamic and innovative artists to include in the book. What became really challenging, 50 artists didn’t feel like enough. I started to realize, okay, I’m going to have to cut an artist whose work maybe doesn’t quite fit. In that process, actually, I realized what the criteria for this book was. I think when you’re looking at a contemporary artist whose defining moment is what kind of influence they have on their people. I started the book with a list of the artists who I thought would be the most dynamic and innovative artists to include in the book. If you take an artist like Amoako Boafo, he’s an artist who’s being celebrated very much by the art market for his very popular portraits of black subjects. It’s work that is extremely topical and timely. In another sense, it interfaces with the whole history of European portraiture that you could say is kind of focused on an artist’s community. In terms of the most rewarding process, it was getting to speak with many of the artists in the book. I would say what was most difficult was trying to narrow down the selection while retaining the diversity and dynamism of the landscape of contemporary African art today.

AS: Definitely. I saw 50, even 50 within West Africa is hard to find a shortlist, much more Africa and the diaspora. Honestly, well done for that because that is no easy feat. You said something about the criteria that you used to pick the artists. Do you use that same criteria when you’re curating for exhibitions for the Tate or any other work, the same format as follows?

OB: Exactly. At Tate, I oversee the Africa Acquisition Committee, which is our committee set up in 2011 to support the representation of African art at Tate and to really provide that same kind of donors with the opportunity. Knowing that Tate Modern’s collections spans the national collection of international art, but is also deeply Western centered in its emphasis, partly because of where the museum is based, but also the kinds of art histories that the museum has prioritized historically. My role at Tate Modern is to try to think about how African artists play a role in the development of the collection, but also how it works. I think a really good example in this book would be someone like Elias Sime, who is an Ethiopian artist based in Addis Ababa running Zoma, a contemporary art museum in Addis, who works almost entirely with electrical circuit boards that are recycled from second hand markets and then recomposed into these abstract grids that could look like modern paintings. In fact using a material culture that’s very specific to the kind of question around sustainability in Addis, and particularly the role that an artist can play in kind of redirecting people’s attention to the way technology kind of connects us as a human race. There are incredibly powerful examples of artists who have perhaps had much longer careers but haven’t really been given the attention that they deserve.

AS: That seems very fair, in giving a chance to people who may not be ready right now but in a couple of years time, they have this achievement to look back on. That they have been in this book and think I’m ready to take a chance now. So that takes me to my question of how you take a chance on how you take a chance on emerging artists while working in the Tate?

OB: I think that’s a really good question about taking a chance on emerging artists, because the one thing I always have to remind colleagues of mine is that it means something very different to be an emerging artist in Lagos or in Accra or in Cairo than it does to be an emerging artist in London. What you find when you look at the book is many of the artists who’ve achieved, you could say, kind of great success, particularly early on, have been artists who’ve relocated to Europe for their university studies and who then have built careers where they’ve been based. Both in the US or in Europe and in Africa simultaneously, all relocated as a result of, family or just kind of general kind of migratory flows. There are some different examples in the book. I think one of the things it’s worth being one of the things I think is really important to be mindful of is that the challenges I think, around developing your practice as an artist on the continent is the lack of institutional space. Since that can support the development. Of course, we’re now seeing more commercial galleries, artists in Lagos, Cape Town Art Fair, Joburg Art. There are some really good examples of local infrastructure supporting emerging talent, but I would say a lot of that support is temporary.

AS: How do you see the future of African arts and African diasporic arts? And what do you hope to see for this field in the coming years?

OB: Well, I would say that what I would personally like to see is more publications like African Art now. I always joke that this book hopefully will have paved the way for people to write Ethiopian art now or Nigerian art now, not because they need to follow the same format. It’s a very general format, but I would really like to see people go into more depth looking at specific national art scenes and local art scenes, because this book had an enormous challenge in a way of having to cover a huge amount of scope, partly because it’s a book that is aimed at a general audience. If you look at the legacy of the Zaria art society in Nigeria made up of members like, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Yusuf Grillo, all of those artists are in fact celebrated as national treasures. But we don’t often preserve their work as if they were national treasures. They become culturally symbolic and we are always happy to celebrate their legacy. What are we actually doing to preserve those works? I think initiatives like the Didi Museum in Nigeria are a really good example of where private individuals are taking up that responsibility.

AS: I’m looking forward to your 2023 show, “A World in Common”. That’s another theme of coming together. What do you hope, being the curator, for us to experience or the first impression when we see the exhibition to be?

OB: “A World in Common” is an exhibition that looks at how contemporary artists have used photography to reimagine Africa’s cultural and historical narratives. It’s an exhibition that takes its point of departure, a more expanded view of African history that doesn’t only look at Africa through the colonial lens, as it was often placed through the history of photography. If you think about Africa’s encounter with photography, maybe the first images taken of African communities and landscapes were, you could say, kind of driven by the kind of of the old industries, let’s say, and photography being one of them. It’s an incredibly ambitious exhibition, but one that I think is going to be both poetic and hopefully inspiring in the way that it brings people into dialogue with the medium of photography. Another thing to say about the exhibition is that it includes looping images and sound. So it’s not just thinking about photographic images as being framed on a wall, postcards, posters, prints, archival documents. All of these different types of photographic material that are present on the continent that we don’t always think of as having any importance. Belgian based artist Sammy Baloji, who in his series memoir and he’s also featured in African art, now takes images from post-industrial images from DRC and then effectively uses a kind of collage technique to impose images of miners and factory workers on these kind of post-industrial landscapes, somewhat creating a tension between the deep history of the Belgian/Congo and the violence of the colonial past and the kind of post-industrial ruins of the present. That’s an artist that I think very successfully is using the archive to imagine different ways of thinking about African history. That’s really what’s at the core of this exhibition.

AS: I completely understand. There’s so much more we have to offer than just the color of our skin. There’s so much more to unearth around that. I feel like because a lot of attention right now on black portraiture is all that people really want to see. Just the blackness as opposed to what that represents being aesthetically pleasing, that it’s black skin. I feel like that really just it’s good to know that there are other people who feel the same way and see it like that as well.

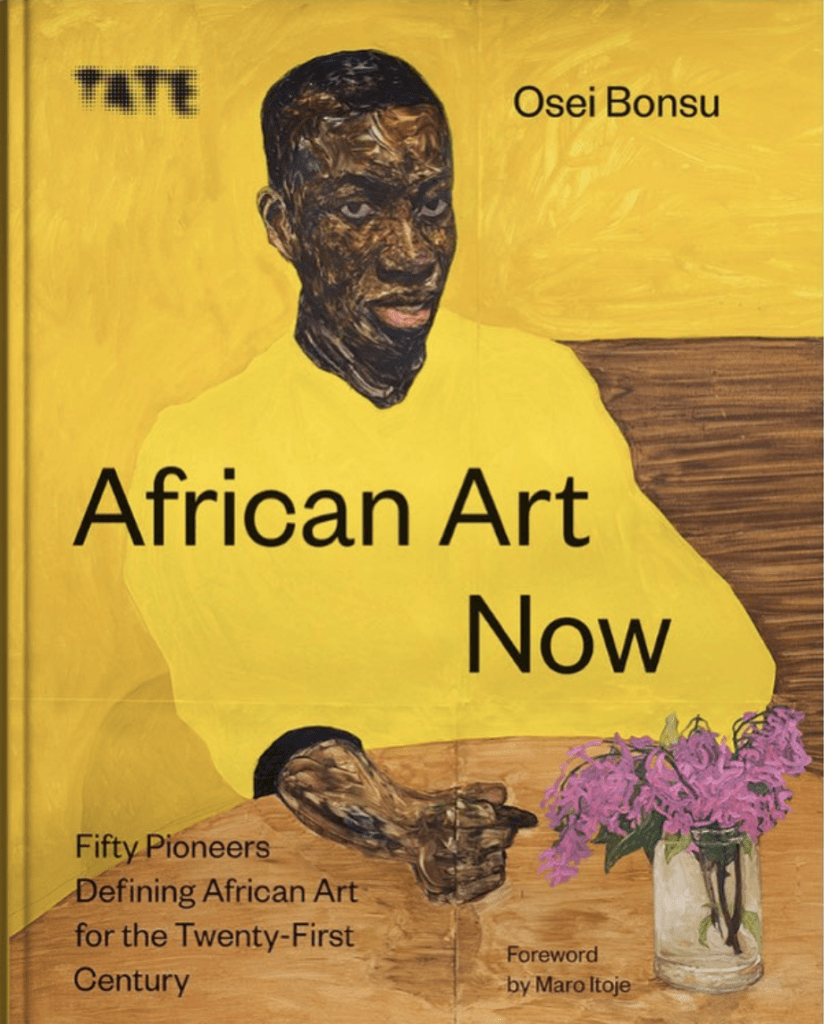

OB: I completely agree. I think that there is a kind of a question that this book is, doesn’t really address, but is present for many of us now, which is if contemporary African art is going to be a global phenomenon that rivals art from other parts of the world or is seen as being part of a global narrative, how do we take ownership of that narrative? When we talk about blackness, many people on the continent don’t really relate to blackness in the same way that we relate to it in the diaspora, in Ghana, when I go home to my family, I’m Ghanaian. I don’t think about my blackness. I think that a Ghanaian in Nigeria thinks even more about being Ghanaian, right? I want to try to create as much space for nuance and complexity as possible, while also reminding people that there isn’t a wrong or a right way to ask a question and that we all should be. I love the idea that people might buy the book because of the cover, it is a beautiful painting, someone in a yellow dress, which looks like a man, but it’s actually a woman. Which I love in and of itself, because we have such strict roles around gender on the continent. When we begin that conversation, we have to make it very clear that it’s a conversation that’s about renegotiating the terms of engagement and that it’s no longer a colonial or a neo-colonial narrative around how Africa should be represented in the world. How quite frankly, people of Africa and the diaspora want to represent themselves.

AS: Renegotiating the terms rules of engagement is exactly what it feels like and that’s just what this book is showing, what we are creating for ourselves.

OB: I feel in many ways as a curator and I’m sure you can feel this as a writer and cultural practitioner, that we’re often in a position of being incredibly responsible for mediating these dialogues between the arts and the wider world. Platforms like yours are really important for that reason, that it might be someone’s first time encountering these artists. How do you tell those stories respectfully, and how do you give as much space for the kinds of narratives that will further deepen people’s engagement with the work and not just engage with it on the surface level, You know?

AS: Yes, I agree. I feel like even personally what I realized, is when I talk to my non art friends, more than even trying to get them to understand respectfully is how to do it without sounding pretentious. So I feel like that is a very key thing that this book does because it’s at your own speed. You read it, you understand it, you can go back to it, which is something I love.

OB: I think that’s key. Someone who might receive it as a present without any intention of visiting a museum or engaging with African art in a you could say in a museum environment. I love the idea that it’s reaching audiences that should know about these works. You might want to learn more about African art. I think that with my intention for that, even in the introduction, for it not to feel like this deeply academic barrier where you open it and you say, “Oh, this book is not for me, it’s for someone with a PhD or a master’s or BA in Art history”. It’s actually none of that because everything that these artists are talking about is in large part a very human issue.

African Art Now is available on Amazon now in kindle and hardcover version here.