Nyaba Léon Ouedraogo, born in Burkina Faso in 1978, is a renowned photographer capturing the essence of African life since 2003. His acclaimed work earned the European Union Prize at the 9th Rencontres de la Photographie in Bamako and a finalist spot for the Prix Pictet in 2010. He also co-founded and co-presides over BISO, the Biennale Internationale de Sculpture de Ouagadougou alongside Christophe Person.

D.C: Can you describe the moment you decided to shift from athletics to photography? How did this transition shape your approach to art and life in general?

NLO: It is indeed true that there is a great leap from athletics to being a photographer. I have two reasons that come to mind. The first is the randomness of things. I stumbled into art by chance. The second is meeting a certain painter, Françoise Nelly. She was a true catalyst for my artistic sensitivity.

I would say that through art, I have been able to discover my own identity. Art has allowed me to discover myself better, to understand myself better, and also to better understand others. For me, art carries within it cultural and spiritual values for each of us. The question I often ask myself is why do I do photography? And the answer for me is that photography allows me to tell human stories in all their dimensions. My photography is one that questions and interrogates our past, our present, and our future.

I do not create photographic replicas; I try to infuse soul into my photographs. That, for me, is the vision.

D.C: Your admiration for Raymond Depardon’s work is evident. How has it influenced your photographic style and storytelling approach?

NLO: Actually, Raymond’s work in “Errance” provided me with some keys. Very early on, at the beginning of my work, I understood the importance of having a vision.

As I am self-taught, “Errance” was like a bible to me in my early days. My photographic narrative leans more towards that of the griot. To be a griot-photographer is to be able to materialize words into images, and this necessarily involves storytelling and the histories of people. That’s why I love the invisible within the visible. The invisible word or story becomes visible through my photography. The conscious invokes the imaginary of reality through creation. For me, creation is divine. The act of creation is mysterious. It surprises me every time. It just comes like that, I don’t know why, even though I master the technique of my medium, which is photography.

D.C: In today’s world, storytelling seems to be everywhere. How would you define storytelling in this context, and how do you differentiate it from mere narration?

NLO: Interesting, interesting, interesting. Your question is both just and challenging at the same time—to find the right words to answer and convey my thoughts. You’re asking me: How can I do the same thing as everyone else and yet have a photographic creation that sets me apart? Is that the question?

D.C: Yes. Also more in a way that your work isn’t just a cliché.

NLO: First and foremost, I believe it’s crucial to be as honest and fair as possible in one’s artistic approach. One must respect the creative process. Many young photographers may think that simply presenting 15 or 20 narrative photographs is sufficient. They are mistaken; it’s much more complex than that. You need to offer a personal narrative that speaks to the universal. That’s what I’ve been doing for the past 20 years: storytelling rooted in my cultural, spiritual, and artistic sensitivity that evokes emotions in others. A good artistic narrative must inherently evoke a strong emotional response. We create art to evoke emotions in others. Through experience, I’ve come to understand that learning to see is not just about opening the eyes but also opening the mind. Personally, I strive to interpret my narrative to its fullest extent to extract emotion.

D.C: Your work often blurs the lines between photojournalism and documentary photography. How do you intentionally balance these elements in your projects?

NLO: To be honest, you are correct, but not entirely. My photographic creation often draws from literary or oral narratives. When I start a project, I strive to deeply understand my subject and gather as much information as possible through oral or literary narratives to immerse myself in what I’m going to propose. For my photographs, I need to be deeply engaged with the project, otherwise, I’m not inspired. I often capture unexpected intentions in the narrative that were planned in the field.

D.C: Your series “The Hell of Copper” brings attention to the dangerous conditions faced by e-waste workers in Agbogbloshie. How has this project affected your views on environmental issues?

NLO: I was deeply moved and saddened when I discovered this place in Ghana. I wondered, why do the richest countries kill the children of the poorest countries? Why destroy the ecosystem by polluting arable lands and making them even poorer? Yes, I realized by asking these questions that I was foolish and ignorant. The Agbogbloshie dump is one of the most polluted places in the world, and the people who wake up every morning to work there often do not realize that it could kill them.

I am convinced that we should approach things very differently to ensure a better future for those yet to be born, to leave them a livable space.

D.C: As a co-founder of the BISO Biennial, what inspired you to create a platform specifically for sculpture in Africa?

NLO: Christophe Person and I founded BISO in 2019 with the aim of providing a space for reflection, creation, and dissemination. Additionally, the platform also aims to incorporate sculpture into the art market, as it is a challenging art form to sell.

D.C: What are your thoughts on the role of art in tackling social and environmental issues in Africa?

NLO: For me, the practice of art is universal; everyone has a sensitivity to art, to beauty. Aesthetics are universal because they are both cultural and spiritual. Art questions and probes the present and future of humanity, particularly in its economic, social, philosophical, cultural, or existential dimensions.

Ultimately, I am convinced that art and environmental issues allow us to come together to question, invent, and share new imaginations in a world undergoing profound changes. Today, we witness a retreat into oneself and nationalism that is observable worldwide. Obscurantism and lack of culture give way to mediocrity and lack of discernment. Groupthink and conformity are beginning to overwhelm us.

The question we must ask ourselves is whether we allow things to remain in this state for future generations.

My answer is that we must act now with conviction because the future is being built now, not tomorrow. Each generation must dare to invent the future. Art is created through questioning and the commitment of all to dare to invent and lay the foundations for a desirable future.

D.C: Your recent work explores themes of identity, animism, and heritage through fictional series. What inspired you to delve into these themes, and how do you approach them artistically?

NLO: The themes I explore are, to me, words or keys that open doors. They materialize in my work as coded images that need to be deciphered. I consider my photographic works as extensions of words, stories, and narratives that I question and interrogate, allowing them never to be closed, to continue to signify, to transmit, again and again.

D.C: What are some challenges and rewards of curating exhibitions like the BISO Biennale?

NLO: The challenges are numerous, but foremost among them is the deterioration of the socio-political and security situation. In addition to armed groups, the lack of funding from our partners can also impact the organization of BISO.

Regarding achievements: The stated goal of BISO is to enter the art world and showcase to enthusiasts and market players (curators, galleries, collectors, journalists…) the richness of artistic production in sculpture in Africa. BISO has enabled several artists to gain national and international visibility and to be represented by galleries in Paris and elsewhere. Additionally, BISO has provided training to over 60 Burkinabé artistic craftspeople.

D.C: What has been the most rewarding project or exhibition in your career so far, and why?

NLO: Well, I’m not quite sure because all the exhibitions I’ve organized so far have been different and equally enriching. In reality, each exhibition is a challenge. Everything is a constant renewal because nothing is ever guaranteed. Perhaps I’ve remained that athlete always striving to shave off a few milliseconds when I press the shutter of my camera.

D.C: How does this exhibition contribute to the broader artistic landscape of Burkina Faso, and what universal lessons do you hope visitors will take away from it?

NLO: Well, this exhibition aims to showcase the contemporary creation of Burkinabé artists and to announce to the rest of the world that we are here. You know that my country is going through one of the most serious crises in its history, particularly struck by terrorism for the past 10 years. I tell visitors to come and see a major artistic proposal from a country that doesn’t have an art school and yet has artists who manage to create high-quality works.

D.C: How do your exhibited works reflect the realities and cultural heritage of Burkina Faso?

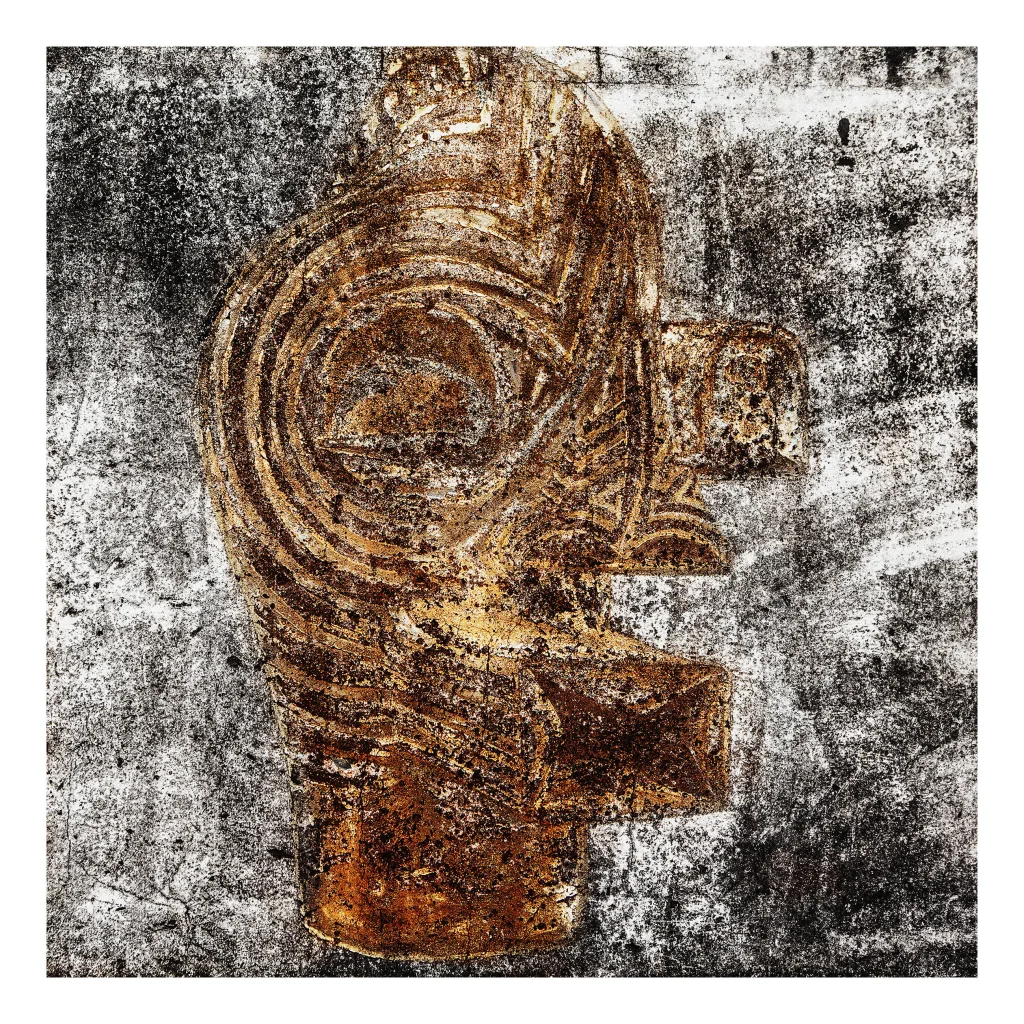

NLO: My works exhibited at Galerie Christophe Person are inspired by the daily life of the Burkinabé people. At Burkina Faso’s independence, Thomas Sankara visited Korea where he got the idea to build a Popular Theater in Ouagadougou, not reserved for the elites but for the people. To adorn the theater’s facades, he asked artists to paint masks representing the different ethnicities of Burkina Faso. After Sankara’s death, the theater fell into decline, becoming home to snakes and salamanders, and its murals deteriorated.

My works question history and transmission in Africa. I challenge current debates on the restitution of African heritage held in the West, given the lack of consideration by local elites for their own heritage. I question why societies that respect their elders so much have so little interest in these signs of the past.

D.C: What reactions or interactions from visitors to the exhibition have been most memorable, and how do they influence your understanding of your art’s impact?

NLO: The visitors’ reaction to the photographic rendering of my work has been very positive. I chose to print the photographs on Hahnemühle’s William Turner paper, which faithfully reproduces the texture of the wall. Many were pleasantly surprised by the quality of the artworks presented. I take this opportunity to thank everyone who came to support us.

D.C: After this exhibition, what new directions or projects are you excited to explore in your artistic practice?

NLO: After this collective exhibition “In the Land of Honest Men” at Galerie Christophe Person in Paris, I will exhibit also with Galerie Christophe Person at AKAA – Also Known As Africa – the first and main contemporary art fair focused on Africa in France. The exhibition will be held at Carreau du Temple from October 18 to 20, 2024 in Paris. Then, there’s the 15th Dakar Biennale 2024 from November 7 to December 7, 2024, which I’m also looking forward to.