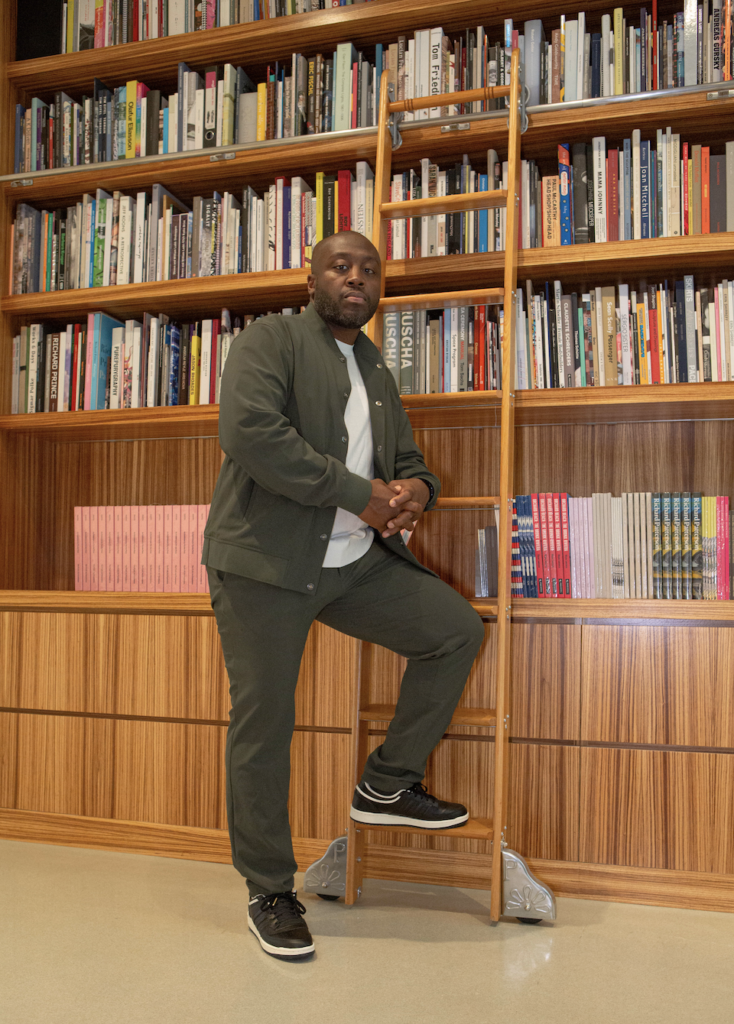

Larry Ossei-Mensah, a native of The Bronx, is also a co-founder of ARTNOIR. A global community of culturalists that creates multimodal experiences for today’s vibrant and varied creative class. Through virtual and physical experiences, ARTNOIR seeks to celebrate the artistry and creativity of Black and Brown artists all around the world. As a curator, Ossei-Mensah transforms how we see ourselves and the world by utilizing current art and culture. He has planned shows all over the world galleries that have featured a number of well-regarded artists. This curator sits with ANA to speak about his career and experience so far.

A.S: How do you decide what artists and what works to include in your shows?

L.O: In terms of how I choose, a lot of it is just based on the concepts of the exhibition and really what’s gonna best execute the ideas. Every exhibition is a collaboration with the artists. It’s also, making or creating space for the artist to respond to whatever the prompt is. It’s not necessarily me going into the studio and saying, “I’m gonna pick these five”. It’s a dialogue with the artists to see what’s gonna best address the question that we were trying to explore through the exhibition. Also what’s the best work for that particular opportunity. I tell artists all the time, just because you made it doesn’t mean it’s good, right? So what is the process to edit and make sure that whatever we show is the best possible work reflecting your practice?

Image courtesy of Courtney Javier

A.S: Not necessarily there’s a theme in mind and they begin to create with that theme or you just happen to see what goes in line with that theme you aim for the exhibition?

L.O: It depends on the situation. Sometimes it’s a theme, sometimes I already have something made and I think if it’s a case-by-case basis there is one particular formula.

A.S: You’re a co-founder at Artnoir, what inspired you to start this initiative? What impact do you have in mind for it in the African art community?

L.O: Well, Artnoir has been around for ten years. It started to support black and brown artists worldwide, ensuring people were aware of their creative expression. For me, it’s an extension of the practice of celebrating writers, visual artists, dancers, and musicians. Making it accessible to all of these artists within all of the spaces. Working with an artist to do a walkthrough of the exhibition, or working in collaboration with a museum, for example, to create tours. It’s really about creating more access and celebrating these creative talents. I’m honored to continue the legacy with my six other co-founders: Danny Baez, Carolyn Concepcion, Jane Aiello, Melle Hock, Isis Arias, and Nadia Nascimento, for the decade.

In terms of Africa, we’ve done stuff in South Africa. During Black Portraitures, we did some talks and some dinners in collaboration with artists based there. It’s always about collaboration and amplifying these voices through the resources in the network.

A.S: It’s been around for 10 years, how would you describe the first 10 years to these last 10 years at which arts has, African arts has really been, I don’t want to say trendy, but finally getting a room in the general global scale of art.

L.O: I mean, I think the last 10 years, we benefit from timing in terms of there being more attention around art from the African diaspora. We want to lean into that. Social media and technology have also amplified that and made it more accessible. Even though you may not be in New York per se, we may post something that gives you a good sense of what’s happening. Or we may do a tour of an exhibition and do it on Instagram Live. Or during COVID, we did the virtual visits, which got you an opportunity to see what it was like to be in another studio. What were they working on? With the aid of technology, we’ve been able to connect more thoughtfully. There are many people that I’ve met through Instagram that I talk to maybe once a week, and I’ve never met or we meet at an art fair. We’re more connected in a way that we weren’t previously.

Now, it’s just kind of making sure that the resources for support is there, whether you are a patron who’s curious about art, an artist who’s trying to get their art out there so collectors can support, a gallery who’s championing the work of these artists, it’s an ecosystem. I think the ecosystem has, for the most part, been attempting to be in service of the artists as much as we are. We’ve started as a group of friends going to see art and we expanded. We gave eight full scholarships to students studying at MFA. We have a micro-grant program called the Jar of LOVE, where we were able to give away $80,000 to people, cultural workers, and artists who needed it during COVID. We currently have applications open for the next batch of microgrants.

A.S: Wow that’s amazing for the community. What impact do you see African arts having on highlighting and fixing social issues within the community?

L.O: Art has always been an avenue to understand the world around us better. By the nature of many artists from the African diaspora leverage materials in their communities to make their artwork. Consider Serge Attukwei Clottey and his use of water jugs within his artistic practice, for example. From a material use standpoint, depending on where you are, you may need access to a different level of materials, or you have some people who want to reject traditional art materials in favor of using local things. In favor of things that are in their community. This approach to art-making opens up the dialogue and the conversation that may not be on the front page news. This ranges from issues around LGBTQI rights, water rights, land rights, and rights for women to issues around visibility and critiques around skin bleaching. So many issues are happening on the continent that artists attempt to engage them. But you also have artists who want to make art, right? And just want to express themselves. And so, I don’t think every artwork needs to be overtly political, but I think it’s more about sharing a point of view and how they see the world. Hopefully, that lens opens up a conversation and a dialogue we want to have, but we may be afraid to have or don’t have the words to. Sometimes art can be that intermediary for those conversations.

A.S: That people’s access to materials is also part of the conversation because it is. That in itself informs someone’s perspective. That is another facet of Africa that the world needs to see, that some people just want to create because they want to and they can. What advice would you give an upcoming curator trying to make a difference in the art ecosystem?

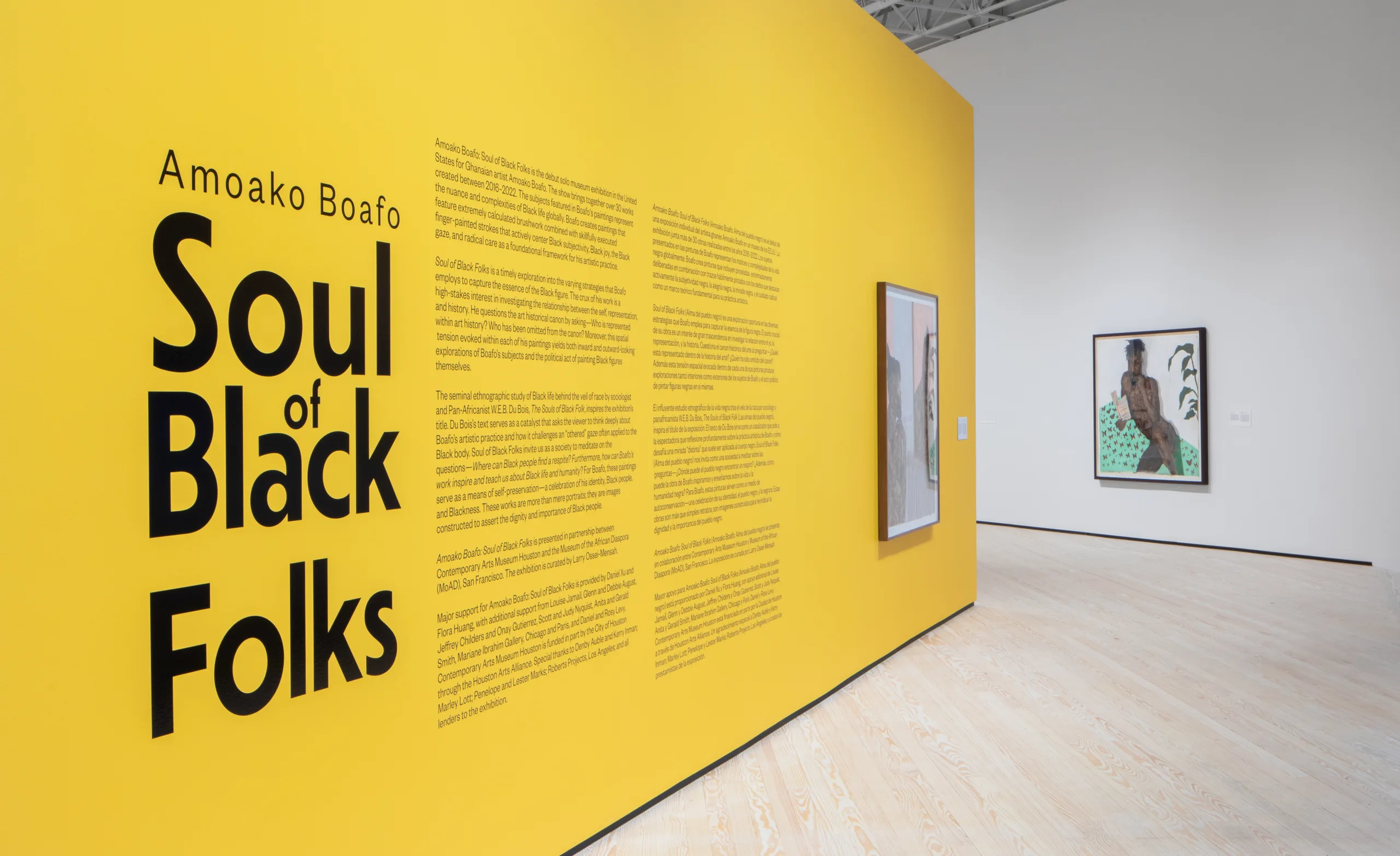

Image courtesy of Tatler Asia

L.O: I would say, make sure that you’re engaged with other curators if you can, whether in person or virtually, make sure that you’re engaged with artists and that your goal is to be in service of the artist’s actualizing dreams, right? The artist is your partner and your collaborator. I think many times, depending on where you are, you have curators who abuse that. They don’t give artists who are talented a chance. I think the curator could be a catalyst to spark exposure around one’s artistic practice. Also, being a curator requires you to be entrepreneurial. Depending on where you live, there isn’t necessarily a formalized infrastructure to support hearings.

How do you collaborate with artists, your community, corporations, and philanthropists, being creative regarding the funding sources you can tap into? It could just be as simple as “ I have this space,” and the space could be in your guest house, somebody else’s house, or a shed that could be utilized as a platform for presentation. There’s a project spearheaded by Dominque Frere called Limbo Accra. They’re an organization doing some cool initiatives in Accra, utilizing art and architecture as an access point for a conversation.

Curatoring sometimes requires not necessarily asking for permission but doing what is important to provide a forum for art and what will stoke the conversation. It’s about community, being creative, entrepreneurial, and using resources that may or may not be there because you can’t necessarily depend on governments for support or grants for support. How do you use your ingenuity to create space for conversations that you think are important?

A.S: I love what’s happening in Accra right now. Its been brewing and now we get to watch it happen. Do you have any upcoming projects that we can look forward to from you?

L.O: I recently curated a solo exhibition by Zeh Palito with Luce Gallery in New York City called Won’t You Celebrate With Me, which was on view from May to June. It was his first solo show in New York. Zeh is an Afro-Brazilian artist who lives between Brazil and Baltimore. In July, I will be collaborating with Amoako Boafo on his first museum show solo exhibition, Soul of Black Folks, that has been traveling across the United States from San Francisco at MOAD to Houston with CAMH and now going to the Seattle Art Museum opening on July 13th. Then the exhibition will go to theDenver Art Museum, opening on October 8th, which will be the last venue for the exhibition. I am also curating my first group show in Brazil, Sao Paulo, called The Speed of Grace Simoes de Assis, which will be cool. It’ll be my first exhibition in South America and Brazil specifically. So I always got things going on.

Moreover, this fall in London, I’ll be co-curating an exhibition called Between the Seams with Paul Anthony Smith at PM/AM gallery. Those are the next upcoming shows I’m excited about putting my energy into. It’s a variety of artists, artistic approaches, and ideas that are being explored in the various exhibitions. I think the public will enjoy it. For those unable to attend the shows in person, I always encourage them to follow my Instagram page, @larryosseimensah. I do my best to tour the exhibition virtually and post images, so even if you can’t be there in person, the virtual experience will give you some insight into what we aim to do with the exhibition.