Afrofuturism, a vibrant fusion of African culture, history, and speculative fiction, exists at the crossroads of history and imagination. Definitely, this cultural movement has emerged as a powerful force in contemporary art, fashion, and literature, challenging oppressive narratives and promoting innovative expressions. In contrast to the constraints imposed by mainstream Western narratives on African art, Afrofuturism boldly reclaims and celebrates African cultural heritage. Art News Africa sat down with Ugandan digital artist and winner of the SABAA Art Award, Denzel Muhumuza (Razaroar) to discuss Afrofuturism’s transformative impact on African art, delving into its historical context and imagining a future marked by continued growth and influence.

D.C: Can you tell us about yourself, your background, and what you do, Sir?

D.M: My name is Denzel Muhumuza, I’m a Ugandan digital artist. My artist name is Razaroar, which is actually the name of my great-grandfather. I had to pay homage to the ancestors, you know.

D.C: That’s interesting. Was your great-grandfather also an artist or was anyone in your family?

D.M: No, he was not. From the stories I heard about him, he was a leader and a healer in his community—one with the natural world. So the ideologies in my work are directly inspired by him and the lives of my ancestors. Now that you mention it, though, I do have a few cousins who are artists and really talented, artistically, but haven’t gone the professional route.

D.C: Yours seems like an amazing family. Your artwork is incredibly unique. How would you describe it?

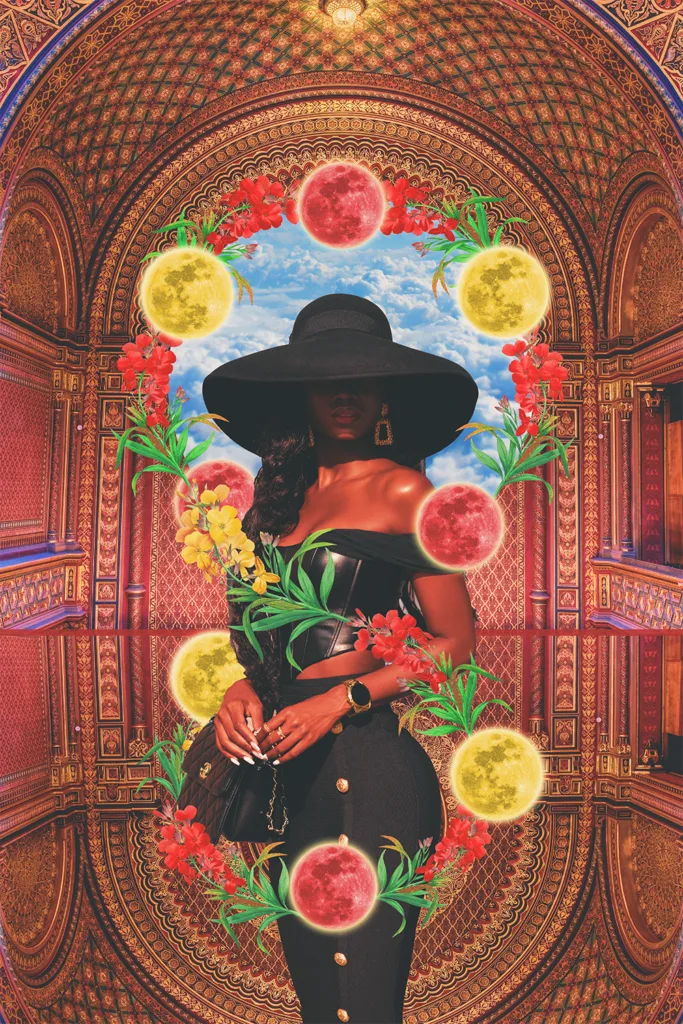

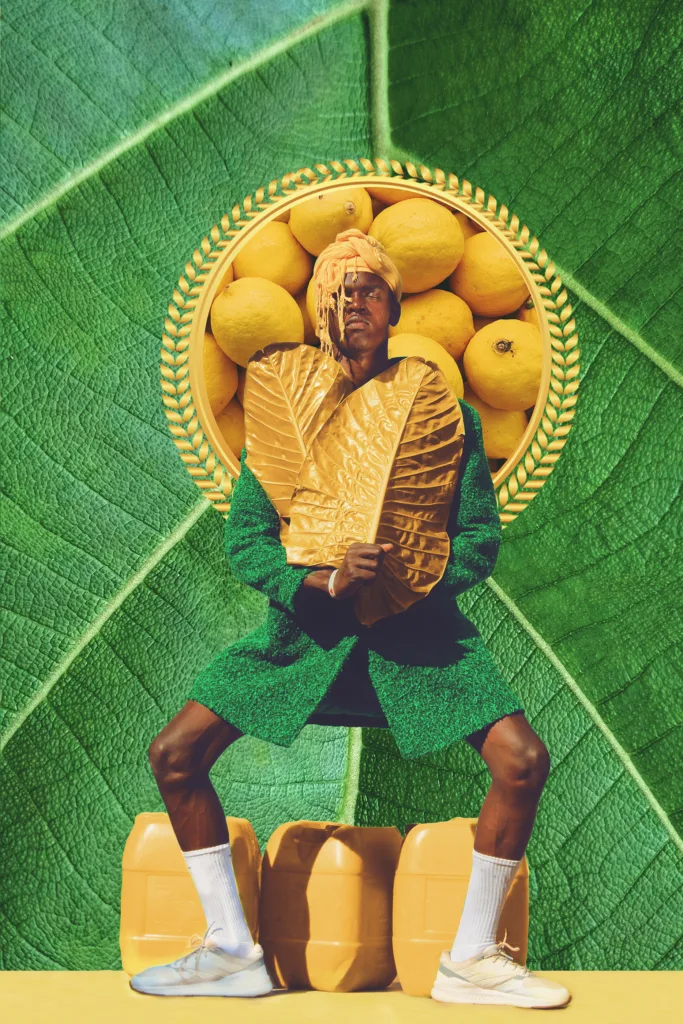

D.M: Yes, I love them to death. Thank you. I would describe my work as a celebration of many things close to my heart. My work is a celebration of the beauty of African people, African culture, and my heritage as a Ugandan. My work celebrates the natural world and the relationship humanity has had and continues to maintain with it. It also celebrates the lives, wisdom, and ideologies of my ancestors and all that connects us. I would describe my work as a reflection of gratitude to the universe, the land, and my ancestors.

D.C: As an Afrofuturistic digital artist, how do you decide on the dynamic graphic elements to incorporate into your digital collages? How do you choose the graphics in your collages?

D.M: Good question! You know, I usually let the spirit lead as I choose graphics. My work celebrates nature, so I always start by thinking about which natural elements I’m going to incorporate into the work—anything from sunsets, rivers, leaves, animals, etc. But with the collection I’m currently working on, I have been very intentional, choosing graphics based on their originality and their relevance to my life, my culture, and my Ugandan heritage. I’ve become very intentional with what makes it onto the canvas and its personal relevance to my life.

D.C: It is clear how much African culture has influenced you, as well as your Ugandan heritage. What role do you think Afrofuturism plays in reshaping the perceptions of Africa on the global stage?

D.M: First, I would like to celebrate the Afrofuturism movement. It is the reason I got involved in creating art in the first place. Afrofuturism is decolonial at its core, helping reverse colonial and neocolonial narratives of Africa and African people. Representation in media is so important, as it shapes not only how you are perceived by the world but also how you perceive yourself. Afrofuturistic art in any medium plays such an important role on the global scale, positioning Africa and Africans as beautiful, powerful, spiritual people with sovereignty over their lives.

It’s so important for us to tell our own stories, create our own narratives, our own fantasies, our own mythologies, celebrate our own spiritual systems, and create our own realities. Afrofuturism helps us connect with our past, pick wisdom from our heritage, and imagine the best possible future for ourselves. And I think this is important not because it reshapes global perceptions of Africa but because it reshapes Africans perspectives on Africa.

D.C: You have worked on political pieces such as “Conqueror of the British Empire” and “Last King of Scotland,” which depict a powerful military black ruler as the ruler of former African colonizers. Could you walk us through the creative process of that?

D.M: (laughs) That I have. Let me walk you through that process so you can understand my personal dilemma. I made those pieces in 2021 but only released them in 2023. Idi Amin was honestly a terrible dictator here, and a lot of Ugandan lives were senselessly lost during his regime. While acknowledging the terrible aspects of his leadership, the artworks invite viewers to experience another side of Amin, one that gets washed away in history.

The work acknowledges his efforts in challenging Western ideologies and asserting African sovereignty. He was a terrible guy, but he was committed to economically empowering Ugandans and achieving sovereignty. In his 1978 speech at the OAU , Amin declared himself the conqueror of the British Empire, claiming he had uprooted British imperialism in Uganda. So yes, he was a terrible guy, but the man was committed to economically empowering Ugandans and achieving sovereignty.

Like many Ugandans, I personally lost my grandfather to the senseless violence of Amin’s regime, and that’s why it took me so long to release the artwork. But after getting some ancestral clearance, I went ahead and put them out this year. While Amin and the regime he led caused a lot of harm to a lot of families in Uganda, there are some policies Ugandans actually respected him for.

D.C: That is insightful. We also get to see Nelson Mandela, Ghadaffi, Thomas Sankara, etc. in “Pan African Dreams.” Do you prefer your art to have its message, or you particularly love to leave it to the viewer’s interpretation?

D.M: You know I try not to be preachy and leave the interpretation to the viewers of the work. But yes, if we are talking about pan-Africanism and pan-African leaders, we really need to include Ghadaffi and Mugabe in the same conversation as Mandela and Sankara. We shouldn’t let Western narratives cloud their legacies.

D.C: What’s your favourite art colour?

D.M: Right now, it’s earth brown.

D.C: Are there specific emotions you love to convey through your choice of colours?

D.M: Yes! Sunshine yellow, for sure. Daytime signifies happiness and positivity in my work. I always use the radiance of the sun to signify outward expressions of contentment and the glow of the moon to represent internal power and spirituality.

D.C: We have been captivated by the prominent themes of landscape and light in your artwork. These elements seem to carry profound significance. Could you share what they represent to you as an artist and how you incorporate them to communicate your artistic vision? Or is it just an “Afrofuturism thing”?

D.M: Peace to the land, for sure. The land is the source of our spiritual power. It’s important for me to honour the land because it provides for us literally everything we need, asking for nothing in return but respect and compassion.

The way we define our relationship with the land defines how we view and treat it. There’s a popular narrative that the land is here to serve us and we are here to dominate the land and take from it whatever we please.

My work highlights the wisdom of our ancestors, recognizing our role as caretakers of the land and animals. Understanding that we are not separate from nature, but one with it. Animals don’t exist solely for our servitude or nourishment. Our ancestors recognized everything has a spirit, not just humans but also animals and the land. I guess it is Afrofuturism at its core because it creates and imagines this future by picking wisdom from the past.

D.C: You are also a rapper, right?

D.M: (laughs) Not anymore, yo! That’s how I got into art, though. When I was a teenager, I started rapping, and it was a lot of fun. I kept at it till university. I made the cover art for my last album, and that was the first time I created visual art. So my art career directly grew out of rapping.

D.C: It’s great to see multifaceted artists. Have you ever had any funny or weird experiences in your journey as an artist?

D.M: Running a business definitely has its weird moments, dealing with customers directly, people commissioning work and then acting like they did not commission the work when it’s time to pay.

D.C: In this digital age where theft and plagiarism are of high concern, especially in digital art, how do you monitor, license, or protect your intellectual property?

D.M: Google alerts are great for seeing where my work is being used online but to be honest, I evade plagiarism by evolving and building on recurring themes in my work so that when someone sees my art anywhere, they recognize it as mine. I currently don’t add a signature to my work, but I do certify all the prints I sell and attach an authenticity certificate with each canvas.

D.C: Also, how is it living in Uganda?

D.M: It’s the absolute best. I was raised here but had to leave for 12 years for school, so I have this immense gratitude to just be here. My family is here, my friends are here, the weather is amazing, the vibes are unmatched! The nightlife is always popping, the concert scene is super dope too. Then nature is unreal here; I went white water kayaking on the Nile this year. Uganda’s true gem is the people though; everyone is good and understanding, even the police.

D.C: Now you make us want to relocate to Uganda. What’s your current go-to music jam?

D.M: Great question, I’m going with “Nothing” by Elijah Kitaka. I won’t lie, Amapiano has me in a chokehold right now. No more hip-hop in my playlists. Just Amapiano, Ugandan music, and Afrobeats.

D.C: Who are the three top artists or art influencers you look up to?

D.M: Tough, tough, tough! It’s impossible for me to pick my top artists, to be honest. I’m such a lover of the arts and look up to everyone killing it. But here are a few artists whose work captivates me: Acaye Kerunen is a big inspiration on the Ugandan art scene. Dolph Banza from Rwanda has a super dope style he has crafted. Then Babajide Olatunji’s work has to be mentioned too. An honorary non-African mention would go to indigenous artist Kentmonkman, a big fan of their concepts.

D.C: What life-learned advice would you give to young talents who want to venture into Afrofuturism via digital art?

D.M: I would advise young talents interested in Afrofuturism to look to the knowledge of the past. Do all the research you can, read academic articles, listen to experts, and ask people you know about their history. You have to learn from the past to imagine the future. Also, focus on the creation of the work, invest time into your craft, and create as much as possible; that’s where the growth is. Manifest opportunities for yourself. Don’t wait for a gallery to back you before you have your first exhibition. Find a way to make it happen with the networks and resources available to you.

D.C: Lastly, where do you see Afrofuturism in the next 5 years, and also where do you see yourself in it?

D.M: Afrofuturism has actually gone quite mainstream in pop culture in the past 5 years, shout out to the good people of Wakanda for that! I see the market and appetite for Afrofuturism growing even further on the mainstream level, which of course is a burden and a blessing. A blessing because the market for Afrofuturism will be much larger, but a burden because messages usually get diluted to reach the masses.

I see myself pushing the Ugandan culture and our African heritage forward on a much higher level, and global scale. Also building community, growing networks, finding new mediums and technologies to tell our stories. Pushing culture forward. Worldwide with it.

D.C: It’s been lovely interviewing you. Thank you for making the time. It was a pleasure talking to you.

D.M: It was actually fun doing this, thanks so much for reaching out and making it happen.

View art collection: razaroar.portfoliobox.net

Contact Denzel Muhumuza on Instagram @razaroar denzelmuhumuza@gmail.com