At the 2025 London Design Biennale will be the prominent display of Wura—a powerful sculptural installation from the Global South Pavilion. Rooted in Yoruba, a language from Nigeria meaning “precious,” Wura challenges narratives, weaving together gold chain, cowrie shells, sound, and oral histories to honor the resilience, complexity, and contributions of the Global South. Danielle Alakija walks us through her process, inspiration and legacy for the project.

A.S: “Wura” means “gold” in Yoruba—why was this name chosen, and what does it symbolize in the context of the Global South Pavilion?

D.A: ‘Wura’ represents the preciousness of Global South culture. Gold in the Global South is not just a metal, it’s a symbol of reverence and worth. I chose this name to start a conversation about how the Global South is seen, not as a region marked by a lack of resources – a false narrative – but as a place rich in culture, history, and innovation. It’s a reclamation of narrative, asserting that our stories are not peripheral to the story of history – they’re integral.

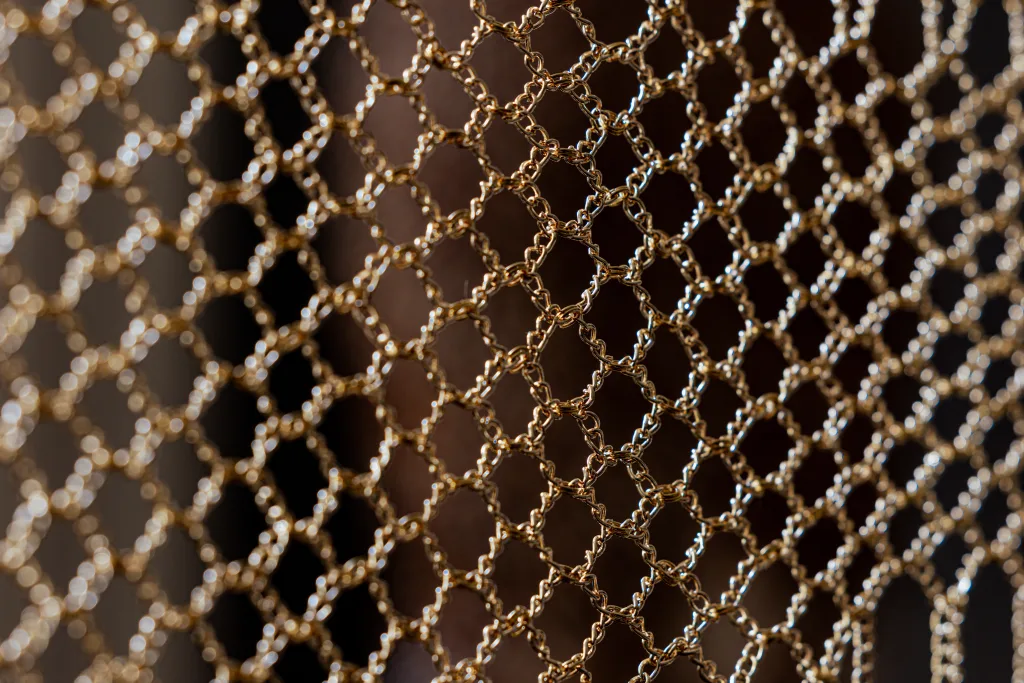

Fashioned from cowrie shells and gold chain, the original currency and the modern standard, this installation weaves together histories of trade, colonisation, and cultural rebirth. The cowries, once used as currency across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, are honoured here as symbols of indigenous economy – rooted in exchange and connection.

The gold chain, delicate alone but strong once interlaced, reflects the fragile identity of a newly defined Global South: powerful, precious, and still in formation. Together, these materials speak to both continuity and transformation – how old systems of value can shape new visions of unity and self-definition.

A.S: Please share central themes and key takeaways the audience can expect to take away from the pavilion?

D.A: The tag line for the Pavilion is “The South Speaks, the World Listens.” That line isn’t just a slogan—it’s a declaration. This piece is about authorship. It’s about reclaiming the narrative of identity and refusing to be defined by frameworks that were never built with us in mind.

I chose the title Wura—which means “gold” in Yoruba—as a way to symbolize the inherent value and richness of identity. It’s a reminder that our cultures, our expressions, and our perspectives are not afterthoughts or footnotes. They are precious. They are central. Despite what dominant narratives might suggest, so much of the world’s creative pulse—its rhythm, its aesthetic, its innovation—draws deeply from the Global South.

At its core, this Pavilion challenges the colonial scaffolding that still underpins much of the global art and design world. It asks: Who gets to frame the problems? Who gets to define the solutions? For too long, the Global South has been seen as a site of crisis, while the so-called Global North positions itself as the problem-solver. That imbalance has led to imported solutions that don’t speak our languages—literally or culturally.

The takeaway here is urgent: we must design Global South solutions for Global South realities. Solutions that are culturally grounded, contextually aware, and structurally appropriate. We don’t need adaptation—we need autonomy.

This is a call for ownership. Ownership of our stories, our aesthetics, our materials, and our innovations—before they are extracted, repackaged, and sold back to us as trend. This Pavilion is a space of resistance, but also of reclamation. It’s a statement that the Global South is not waiting for permission to lead. It is already leading—with voice, with vision, and with value.

A.S: As a British-Fijian-Nigerian artist, how has your multicultural identity shaped your vision and process in Wura?

D.A: One of the most common refrains these days when discussing art is the idea that we should “separate the art from the artist.” But for many of us—especially those from historically marginalized or diasporic communities—that separation is not only unrealistic, it’s a denial of lived experience.

My identity isn’t something I can set aside in the creative process. It is the lens, the foundation, and the framework through which this installation was conceived and realized.

Wura was never just a conceptual piece—it was an embodiment of where I come from, who I am, and the worlds I navigate. As an artist whose heritage spans much of the Global South, I felt a deep responsibility to ground this work in materials and stories that reflect that multiplicity. Every element in Wura was chosen with intention. The cowrie shells, which form a core visual and symbolic structure of the piece, were sourced from across Africa, Asia, and the Indo-Pacific. These aren’t just ornamental choices—they carry weight.

The shells vary in species, size, and tone to signify the wide-reaching geography of the cowrie’s history: used as currency, as ornament, as spiritual symbol, and as a tool of colonial extraction. Their presence in Wura speaks to trade, migration, and exploitation—but also to resilience, continuity, and adaptation. They are artifacts of both beauty and burden.

A.S: What was the specific moment of inspiration, when it hit, that this was the idea for this pavilion?

D.A: I’ve always been fascinated by fishing nets—the way individual threads, fragile on their own, become something far stronger and more resilient through their interweaving. That metaphor of connection, tension, and collective strength has always stayed with me, and it’s at the core of Wura. This piece is the second in a three-part series exploring material, memory, and identity. The first work, Iyau, is a wearable sculpture crafted from the same material composition—cowrie shells and gold chain.

Growing up in Fiji, cowries were more than decorative objects; they were symbols of exchange, beauty, and meaning. They held cultural, economic, and even spiritual significance. That early exposure shaped the way I’ve come to understand material as a vessel for story. Cowries, once used as currency across Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, represent not only a form of indigenous economy, but also a shared language across many parts of the Global South. Bringing Wura to the London Design Biennale was more than just an opportunity to showcase an artwork—it was a chance to reframe how the Global South is seen on international stages. Too often, our regions are referenced as inspiration but rarely given authorship. Yet the roots of so much global creativity—lie in the Global South.

A.S: What were some key considerations in approaching the design for this project?

D.A: Personally, my favorite part of the design process is that first act of making—when an idea begins to take physical shape. Ideation is beautiful in its own way; in your mind, everything fits. But the moment you start building, the potential flaws of physicality become apparent. You’re confronted with the resistance of the physical world—weight, tension, scale. That’s where the magic lies. It’s in problem-solving, in adapting, in watching something evolve through your hands, not just your thoughts.

With Wura, that process was even more layered. This wasn’t just about making an object—it was about building something that could hold the weight of many histories, many voices. The challenge wasn’t only technical; it was cultural. The project needed to represent a diverse expanse of the Global South, while still honouring the uniqueness of each region. There’s always a risk, when working across such a broad scope, of flattening differences into generalities. I was determined not to let that happen.

A.S: How do you see this installation contributing to larger conversations around decolonizing design and cultural institutions?

D.A: Too often, design institutions and cultural platforms borrow from the Global South without crediting or deeply engaging with its context. This piece disrupts that pattern. It reclaims space, not just symbolically but physically, by placing indigenous materials like cowries—once a form of currency and cultural exchange—at the heart of an international design conversation.

By weaving together elements that speak to both historical trade and contemporary value systems, Wura challenges the dominant narratives that have long excluded or extracted from our communities. It reframes the Global South not as a passive source of inspiration, but as an active, foundational force in global design. In doing so, it calls for institutions to rethink what they value, who they center, and how they engage with histories that are still very much alive.

A.S: What are the next steps for Wura as it travels to the Global South?

D.A: It was incredibly important to me that Wura did not end with the London Design Biennale—that it lived on, evolved, and continued to resonate long after the event. The Pavilion was never meant to be a static exhibition; it is a living archive, a breathing, responsive space rooted in memory, identity, and resistance. It reflects not only a specific place, but the layered cultural histories, political realities, and generational narratives that shape that place.

This isn’t just about architecture or design—it’s about the power of space to tell stories that have too often been erased, overlooked, or distorted. The stories embedded in Wura cannot and should not exist in a vacuum. They demand context, engagement, and expansion. They must move beyond temporary installations and surface-level representation.

To do that, we have to challenge and go beyond the existing frameworks—especially those rooted in Western-centric models of curation, preservation, and participation. We need to imagine and build new infrastructures that are created by and for the Global South. Infrastructures that aren’t just imported systems with localized tweaks, but ones that are engineered from the ground up with the realities, needs, and potentials of these communities in mind.

Wura will be travelling to Nigeria at first, and then carrying on to Southeast Asia and we hope Latin America in order to create this infrastructure we so desperately need.

A.S: What kind of legacy do you hope Wura will leave behind—for the design world, and for the Global South more broadly?

D.A: I hope Wura disrupts. I hope it forces a confrontation with the colonial foundations still embedded in how we design—whether it’s cultural, structural, or political. Too often, these systems are treated as neutral, when they’re anything but.

Wura challenges that. It asks us to reflect on what we inherit, what we choose to carry forward, and how we define value in a world still shaped by its past. It’s an invitation to rethink worth—not through the lens of extraction or legacy power, but through memory, connection, and cultural truth.

It doesn’t offer answers—it opens space for new questions, new visions, and new ways of building.