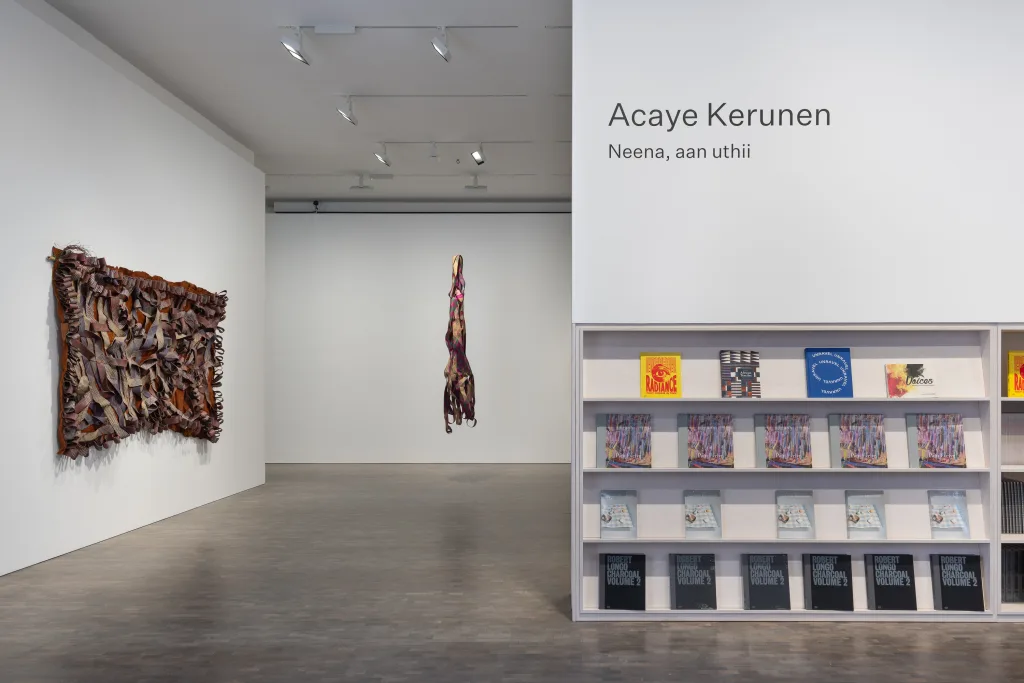

Acaye Kerunen presents her debut solo exhibition in the UK at Pace Gallery, titled “Neena aan uthii.” Translated as “See me, I am here,” this exhibition affirms her identity as a child of East African soil. This exhibition features diverse sculptures, installations, and performances that pay homage to East African communities. Uganda, Kerunen’s homeland, inspires her choice of materials and artistic creations. The sisal plant, used for making traditional kiondos in Eastern Africa, is a key material used in her works. ANA speaks with Acaye about her creative process, inspirations, climate action, and more. The exhibition runs from January 15th to February 22nd, 2025.

R.M.: Can you elaborate on the deeper meaning of this exhibition?

A.K: Neena, Aan Uthii- translated from alur means See me, I am Here /Present. I aim to manifest my artistic vision and inspire others to create, curate, and exhibit similar points of view to mine despite a lot of ill will, and attempts at misrepresentation, especially from the place I call home.

The British Library and Africa Museum in Brussels were extremely triggering and depressing for me. Their African collections had disturbing histories of collection. For instance, the Luzira Head from Uganda who is now entombed in an airless glass vitrine at the British Library is suffocating in a static zone. At home, where it was extracted from in Luzira, it used to be an active and mobile artifact through ritual. It was molded by sacred hands, processed through the ceremony, and buried in enshrinement. Only for it to be unearthed and the site of its find turned into a maximum prison by the British colonial government.

This exhibition invites a new kind of experience, a contemporary and purposeful contact through presence alongside performance and music with viewers being invited to feel free. For a very long time, I struggled with anxiety while singing because my mother’s voice, which was my biggest inspiration but also my biggest foe, had implanted her voice of disapproval in my head. She often reprimanded me to keep quiet, because she always complained that my voice was too loud. So, I sang a lot from my head voice, in secret.

The same way that colonial education instils disdain for our cultural heritage art and materials. This journey to escaping from beneath the heavy rock of such misguided projections of power as wrong, different as wrong is embedded in the title. It also includes my bold response to all these in materiality as well as in the track/song Eyaah which, I performed last at the opening. That song is my psychedelic journey through tonal resonance to liberate myself from a negative matriarchal gaze and voice as well as from the squinting Western and Ugandan gaze upon my art.

Again, by extension, it’s the journey of many women I collaborate with who are frowned upon when they indulge their inner children to make playful things that are not necessarily functional or to dance freely. Whom they now keep sending to me for mentoring, guidance, and counsel. Their collective stories, told, observed, felt inspire the work. That, and the landscapes, environments, and philosophies that underpin their making.

This exhibition is also a response to colonial art education which I thankfully did not receive. Yet were compared against as if they were the same. With this exhibition, I include the numerology of making, the poly-mathematics of structure, the science of color, and the resilience and versatility of natural materials and regenerative knowledge from my lived and learned heritage experience. This exhibition is therefore a provision from me to the artistic canon of Uganda and the Western world of what should be included in their education syllabus.

I was never who the art world of Uganda expected to be here now in this way on the world stage. Their eyes and support were elsewhere, to other artists whom they believed “better represented ‘them’: yet here I am anyway.

R.M: There is a diverse use of materials from Uganda and the better part of East Africa, could you elaborate?

A.K: The materials I choose and the contexts of their making, now take center stage globally in different and similar iterations. This is through smart ecological practices, co-existence with nature, respecting time through the natural cycles of life, and not industrially rushing things in the name of development at the expense of the universe which is literally on fire right now.

R.M: What do textiles mean to you personally, beyond their functionality?

Textiles are the material extension of life, identity, and community to me. A strong memory and experience I carry around is of a handstitched kitenge skirt that mommy made for me and my sister. She had been gifted the textile from Congo and used what was left of it after she fashioned her garment to make our skirts. Friends’ mothers kept asking us to ask Mommy to show them who the tailor was because they could not tell the difference, in stitch quality with the machine-sewn garment. I became a textile designer from self-led design and mathematical realization to arrive at patterns and designs, some of which pop up in my work often. I watched her cut and sew those straight skirts that I wore until my body grew out of them.

The collective sculptures in my works explore individual functional materials as zones of nuanced meaning-remaking. This is due to their mobility from the wetland habitats to the harvesters, the traders, the buyers, the makers, and finally to me. Then, on their onward journey as amalgamated sites after I remake them to the courier, then to the gallery, and finally to their different collectors and audiences.

Through their movement, a ritual chain of production and supply becomes a part of their story. By being at Pace, Kandlhofer, Blum galleries, as well as at the Barbican, Venice Biennale and, all the art fairs they show at, they acquire new meanings as they crisscross racial, political, cultural, and academic borders. A lot of the grain and harvest baskets fascinate me by their architectural shapes, and function with specific braids, weaves, and knots to suit particular purposes.

R.M: This exhibition feels incredibly necessary. Who or what inspired you to create this exhibition, and why?

A.K: My biggest inspiration is my mom who was a practicing artist herself. Yet she did not consider me good enough. She had no patience for my learning process and proffered it to my elder sister. In vainly seeking her attention and approval, I became my multimedia artist from the shadows of her gaze. By extension, I see her in other women and understand them and their daughters better too.

I am beset with a story that will not leave me alone unless I tell it severally; through works and creative babies. The ideas for these creative children keep inviting themselves into my mindscape and refusing to leave. A lot like our extended family visitors at home who would show up, unannounced, in the earliest hours of the day and refused to leave until they were served dinner. Moreover, with performative respect, delivered by the females through kneeling, serving, cooking, etc.

R.M: Who inspired you to nurture your femininity despite all this?

A.K: My most profound role model in balancing feminine and masculine energy is the late Renuka Pilay She was my employer and mentor at the Basic Education and Policy Support Project (BEP/SUPER ) at the Ministry of Education and Sports 2005/6. She headhunted me and created a role for me as a Disability Education Assistant at the project. I have been doing a lot of advocacy for girl child retention in schools in various districts of Uganda. Word spread about this girl doing out-of-the-syllabus activities that were working. In this role, I answered directly to her and the line commissioners within the Ministry of Education. She relayed this to me one day over a cup of tea. I had already got the job.

She was one of the most influential and powerful personalities in education transformation for Uganda between 1996 and 2009, yet one of the most feminine people I ever met. Soft in a beautiful, powerful way. She asked me, “Who lied to you that softness is weakness? Find the light in every moment. There is a lot of it when you open your eyes…’’ Renuka. Hence my chosen theme of joy in all my work.

I saw her switch fluidly from influencing policy in a government boardroom to brewing a cup of tea for her partner with grace and humility. She loved all and served all with grace. Getting acquainted with her, and working under her leadership opened my eyes to a world where aggression, abrasion, and defensiveness never need to be allowed to thrive beyond their survival seasons in my life.

The more I realize myself, the less I need to survive from a place of reactivity. The softer and more rounded in response I also become through existing.

R.M: Uganda, the Pearl of Africa, boasts lush greenery. The use of flower hues, ash, and grasses in your work denotes an intimate relationship with the work. What do these elements mean to you?

A.K: They are a repurposing of my childhood memories as a forager. Before Kampala became less green, I lived in a neighborhood with woodlands and mini forests. I spent countless hours in the bushes, watching mostly birds, finding ripe fruit. These colors in their natural opulence continue to inspire me. I learned the language from my childhood.

Color as an evolving radiance also allows me to repurpose my love for chemistry as a subject I took for a while in school until I dropped it due to sexual harassment by my teacher.

R.M: As an artist, how do you nurture artistic skills and creative instincts within you as part of the global community?

A.K: The child within me makes all the artwork. The adult self is always questioning why. The child simply follows the thread of inspiration to its end. We need to allow ourselves to honor the child within. To allow her to dance, to play, to sing even though the voice breaks or shakes. As well as to dance often like no one is watching.

R.M: What is your favorite piece from this exhibition, and why does it stand out to you?

A.K: I have no favorite, but the music is still a tender spot. That performance was a big trembly moment for me. I faced my mum with dignity and respect. I shut out her voice, turned away from her gaze, and sang my music.

R.M: Much of Africa experiences distinct, predictable seasons. On a recent visit to my rural home, I noticed that the seasons I saw as a child persist. What are your thoughts on climate change agendas in Africa?

A.K: We need to drop the politics around it and do the practice with women as the lead. I mean the community women who know the land and her seasons better than most.

R.M: Do you think we need external interventions, or should industrial development take priority?

A.K: I think we should drastically reduce them. A lot of pollution of our waterways presently is from industrial waste by large foreign companies in the name of economic development.

R.M: What keeps you motivated in your artistic journey?

The innate knowledge that this is my moment, this is my time, and not to waste it. I am blessed to be represented by a major gallery a first in many ways for East and Central Africa. Importantly, I enjoy open circular conversations with them all and they cohere for my best interests. This sincere love and genuine support move me to excel and to give my best always.

R.M: As a woman from Uganda, part of Africa, and the global community, what has your journey taught you?

A.K: Laugh completely, cry, say goodbye once; not many times over to the same things, people, spaces. When leaving, depart with a smile, you just might return with a need for it. I have learnt that No one is coming to save me and that I have to save myself first; before attempting to save others.

I have created an Acayeism with my artmaking like Lee Ufan created an ism (as Ashley Dugan, my Liaison from Blum explained. He was telling me why I am represented by Blum after I asked him ‘why me’ in representation).

That took courage, time, and a lot of resilience. Now literally everyone who is making art or curating art from my region imbued with natural materials and regenerative practices finds themselves beset with the dilemma of having to reference themselves, or to be referenced by others through my work. It is both a privilege and a burden.

R.M: What lessons do you hope to pass on to the next generation of young writers, scholars, and artists?

A.K: I have a few lessons;

- Visibility is a privilege and a trap. Try not to fall into the trap. Keep doing, keep refining your art consistently and with integrity. Don’t only stop at asking why, ask why not as well often, deliberately.

- Be content, respectful yet grounded, and thankful at every step of the way.

- Own your No’s. Do not work with desperate people. Detach from envious colleagues. Their season in your life is over when that happens.

- Art always makes a way even where there seems to be no way.

- Go where you are welcomed and celebrated, not where you want to be. Speak less. Do more.

R.M: Is there a famous quote from an African heroine or someone who inspires you that resonates deeply with you?

A.K: ‘’ You are royalty by lineage and heritage. Live up to that legacy. Don’t allow circumstances to make you less. Use your gifts as your way makers” a rephrased statement from my mum to me and my sister when we were going through a very rough patch. These statements have never left me.

R.M. What is your hope for the next generation of young women in Africa and beyond?

A.K: I hope the next generation, my children included are less afraid than most of us have been to ask why not. Instead of stopping at why. I also hope they take with them, from us the disappearing human value of discipline and the respect of time as a process. Most of them are rushing, careening towards an abyss of regret and irreparable damage in drug and substance abuse, and various addictions in the name of instant gratification.

R.M: Finally, do you have any words of encouragement for emerging writers, artists, and curators?

A.K: Listen from some, especially those who have walked your path before. Reject the noise makers. There are many of those. If I had accepted all the noise about why or how I should not do it in curating and producing the second Uganda Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, it would have never happened. Neither would I have learned what I know now about budgeting, and international curation for the biennale of which I am the only one presently from Uganda with hands-on experience, human nature, strategy, diplomacy, and more.

Good writing is rewriting. Good making is remaking, good curating is recruiting your curation. The way will always reveal itself. But you must take that first step to keep walking, writing, coordinating, and articulating one day, 3000 words become 20 poignant lines of statements that outlive you.