Emerging from the rich sculptural traditions of the Urhobo people in Nigeria, Ejiro Fenegal has quickly distinguished herself as a contemporary artist who bridges heritage and innovation. Her debut solo exhibition, Makers of Legacy at Mitochondria Gallery, celebrates the strength, resilience, and presence of African women through monumental sculptures cast in bonded marble. Drawing from personal muses, historical references, and cultural memory, Fenegal’s work transforms traditional forms into contemporary statements about identity, continuity, and empowerment. In the following conversation, she reflects on her practice, her inspirations, and the stories that shape the women immortalised in her art.

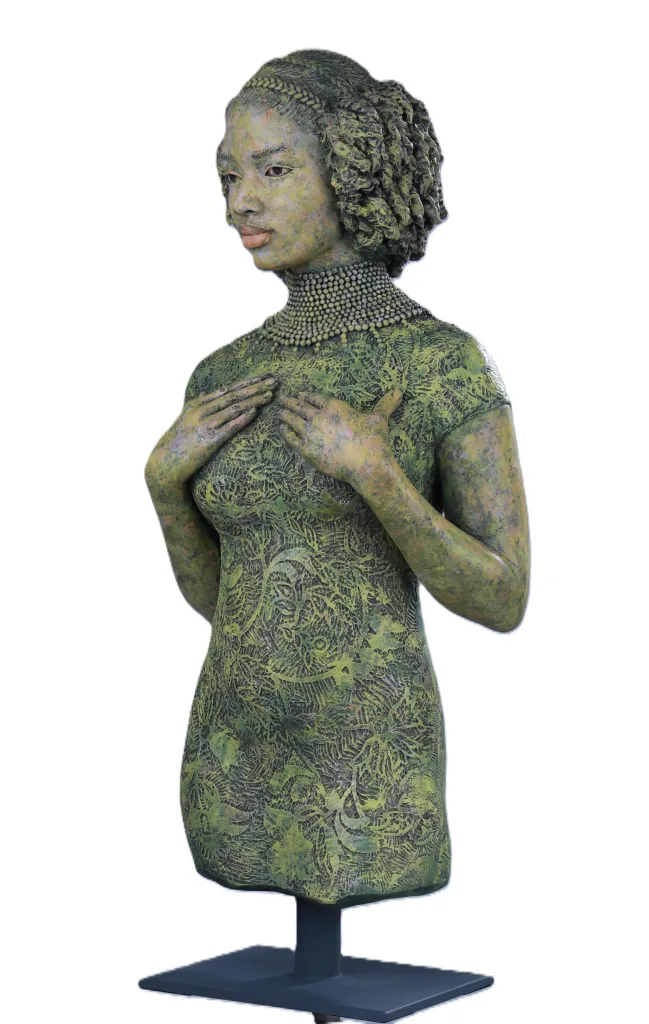

Resilience, Bonded Marble, 22 x 11 x 11 inches, 2025

T.E: Makers of Legacy is your debut solo exhibition. What does it mean for you personally to

present this body of work at this moment in your career?

EF: Being my debut solo exhibition, “Makers of Legacy” is a dream fulfilled. This moment marks a step closer to what I have always hoped and prepared for as an artist. Presenting this body of work now feels like an opening, a space for growth, for reflection, and for a deeper commitment to my practice. It is not only about showing the works, but about claiming my place as a voice among sculptors and women artists from my community and beyond.

T.E: In your artist statement, you write that every woman is “worthy of being cast in stone.” Can you talk about how this belief shaped the making of these works?

EF: That belief guided every decision in the studio. For me, it is not about celebrating only the extraordinary woman, but recognizing that every woman, whether her life is quiet or public, is shaping legacy. By choosing to sculpt women in durable material, I am making a statement that their worth, their struggles, and their contributions are not fleeting. They deserve permanence, the same reverence historically given to kings, warriors, and deities.

Image courtesy of Mitochondria Gallery

Image courtesy of Mitochondria Gallery

T.E: The exhibition focuses on women as “makers of legacy.” How did you select the muses for your sculptures, and what role do their personal stories play in the final works?

EF: The muses are women around me; mothers, daughters, leaders, quiet fighters, and everyday

women whose lives carry a certain weight of meaning. Some are family, some are friends, and

some are women I have encountered in passing but who left an impression on me. Their stories are

not always told directly in the works, but their presence is there in the gestures, the postures, and

the emotional language of the sculptures. Each piece becomes a vessel that holds part of their

strength and struggle.

T.E: Your practice is rooted in Urhobo sculptural heritage. How do you see your work as a continuation of that tradition, and where do you feel you diverge from it?

EF: The Urhobo tradition grounds me. Our sculptural language has always carried depth, spirituality, and strength. I see my practice as a continuation of this legacy, preserving the sense of form, presence, and storytelling that comes from my heritage. Where I diverge is in how I center women as the primary subjects. Historically, women’s stories have not been given full visibility in sculpture. By focusing on them, I am both honoring tradition and reimagining it for today, expanding the lineage to include the strength, resilience, and complexity of women’s lives.

T.E: Many of your sculptures embody tension between softness and strength, visibility and silence, duty and desire. How do you navigate and communicate these dualities in form?

E.F: These dualities are part of being a woman, and part of being human. In form, I often play with balance; delicate features held within strong bodies, or monumental presence contrasted with subtle expression. I allow clay or bonded marble to reveal both fragility and endurance. I think of these tensions not as contradictions but as truths that coexist. By holding them together in one form, I want the viewer to feel the complexity of women’s lives without simplifying it. The foreword situates your work alongside figures like Akpojivi Orhokpokpo and Bruce

Onobrakpeya.

T.E: How have these masters influenced your approach, and how do you position yourself within that lineage?

E.F: These masters taught us that art is not just about form but about meaning and inheritance. Akpojivi Orhokpokpo’s sculptural presence and Bruce Onobrakpeya’s experimental spirit both inspire me. They remind me that to create is to carry forward history while also daring to invent. I see myself as part of that lineage, but I also feel a responsibility to stretch it, to bring women’s voices, faces, and bodies into spaces where they have not always been centered.

T.E: Your works sit within a global discourse on African art, where there is often tension between

heritage and contemporaneity. How do you want international audiences to engage with your

sculptures?

E.F: I want international audiences to see my work first as human stories, then as cultural expressions. Yes, they are rooted in Urhobo heritage, but they are also conversations about resilience, womanhood, and identity that transcend borders. I hope audiences engage with them not as “exotic” but as part of a global language of sculpture, where heritage and contemporaneity are not opposites but partners in dialogue.

T.E: Finally, the title Makers of Legacy suggests continuity but also responsibility. What legacy do you hope your own practice will leave for women, for Urhobo culture, and for the broader field of sculpture?

E.F: I hope to leave a legacy that women can recognize and hold onto. Growing up as a woman in any community, you must know within yourself that you have a role to play. You must know that life is not for spectatorship. We are here to contribute, to shape, to build. For women in particular, the journey may feel more complex, but determination makes it possible. I want the women of Urhobo land, of Nigeria, of Africa, and beyond who dream of being sculptors to know they are not weak vessels. They can push past doubt and aim for excellence in fields where society might not expect them to stand. Sculpture has long been seen as a male domain, but with my practice, I want to open doors. My hope is that the legacy I leave will be one of courage, strength, and a widening horizon for women and for sculpture itself.