In the world of contemporary African art, the unfinished is not a flaw but a statement. An incomplete portrait, a rough-edged sculpture, a half-told story—these are not accidents but deliberate artistic choices. They invite questions rather than offering answers, leaving space for interpretation, dialogue, and reflection. For many African artists, incompleteness mirrors the lived experience—personal histories disrupted by migration, colonial legacies that left cultural narratives fragmented, and societies still in the process of reclaiming their voices. Rather than seeking resolution, these artists embrace ambiguity, allowing their work to reflect the open-ended nature of identity, history, and memory.

But what does it really mean when an artist chooses to leave a work “unfinished”? And how does this artistic device shape the narratives being told?

Historical and Cultural Context

The notion of incompleteness is not new in African art. Traditionally, African storytelling—whether through oral traditions, textiles, or sculpture—has often been nonlinear, open-ended, and interactive. In many societies, griots (oral historians) would adapt stories depending on the audience, leaving narratives unfinished so they could be continued by future generations. This philosophy of openness translates seamlessly into contemporary art, where incompleteness reflects not only personal artistic choices but also broader cultural themes.

Moreover, colonial disruption left much of Africa’s history fragmented. Entire cultures were uprooted, artistic traditions were interrupted, and histories were rewritten. Contemporary artists have found power in reclaiming that fragmentation, using unfinished works to critique historical erasure and highlight the ongoing process of cultural restoration.

How African Artists Make Use of the Unfinished

Contemporary African artists employ a range of techniques to convey incompleteness—unfinished brushstrokes, missing facial features, raw and exposed materials, and layered compositions that seem to dissolve into abstraction. These visual strategies create a sense of openness, allowing viewers to project their own interpretations onto the work.

For example, Nigerian artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby blends detailed photorealism with areas of faded, fragmented imagery in her paintings, symbolizing the fluidity of cultural identity between Nigeria and the West. Similarly, Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu uses collage to create hybrid figures, where parts of bodies are missing or replaced with unexpected elements, reinforcing themes of dislocation and reinvention.

Contemporary African Artists Who Have Mastered the Art of Incompleteness

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

British-Ghanaian painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye is known for her evocative portraits of Black figures—yet none of them actually exist. Her subjects are fictional, drawn from memory, imagination, and intuition. The vagueness of their identities, coupled with her loose, gestural brushstrokes, gives her work a dreamlike quality, as if the figures are still taking shape. By not tying them to specific narratives, she invites viewers to create their own stories, making her portraits both deeply personal and universally resonant.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s portraits are captivating not because of what they reveal but because of what they withhold. In A Passion Like No Other (2012), she presents a lone figure in muted tones, his expression unreadable, his background undefined. There is no clear narrative—only hints, suggestions.

Her choice to paint fictional figures, unmoored from specific histories, allows the audience to complete their stories. In leaving them ambiguous, she challenges the Eurocentric tradition of portraiture, which often aims to define and categorize its subjects. Instead, her figures exist in a liminal space, resisting easy interpretation.

Ibrahim Mahama

Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama repurposes old jute sacks, stitching them together to create massive installations that envelop entire buildings. These sacks, once used to transport goods like cocoa and charcoal, bear the marks of trade, labor, and time. By leaving them raw and visibly worn, Mahama highlights the unfinished work of decolonization and the lingering inequalities of global trade. His art is a reminder that history is still being written, and the struggle for economic justice is ongoing.

In his piece Non-Orientable Nkansa (2016), Ibrahim Mahama doesn’t just create an artwork—he builds a living archive of resilience, labor, and survival. His installation, made from wooden shoeshine boxes known as nkansa collected from the streets of Ghana, stands as a chaotic yet deeply intentional structure. Each box, worn from years of use, bears marks of its former owner. Some are splintered, some barely holding together, yet Mahama does not fix them. He does not smooth out their rough edges or repair the broken ones. He leaves them as they are—unfinished, imperfect, yet powerful.

By refusing to impose a polished, final form on the structure, Mahama forces the audience to reckon with the reality of Ghana’s working class—young men who shine shoes, repair them, and drum rhythmically on their boxes to call in customers. He takes what is seen as disposable, as background noise in Ghana’s busy streets, and makes it monumental. He forces us to look at incompleteness not as failure but as a narrative in motion, as a story still forming.

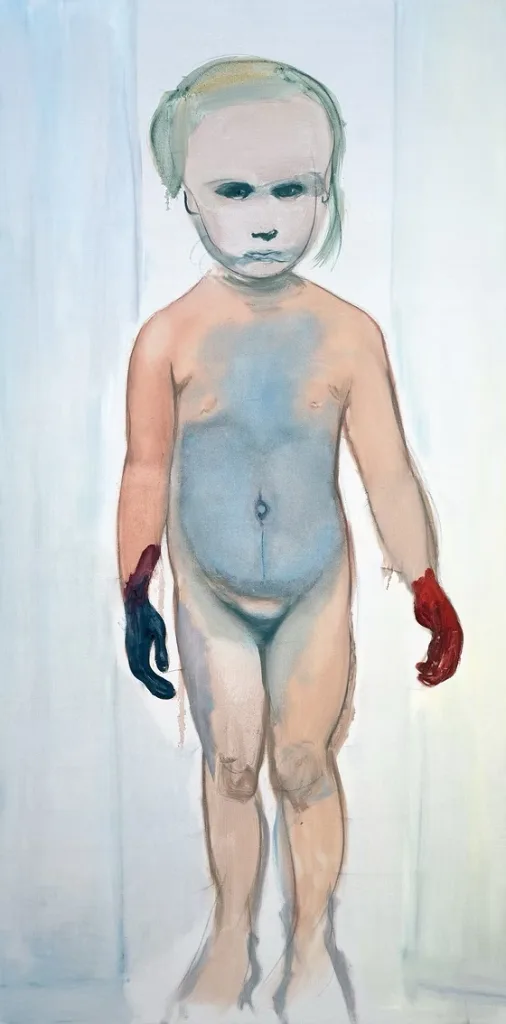

Marlene Dumas

South African painter Marlene Dumas embraces the unfinished with her haunting portraits, often leaving faces and bodies half-formed or dissolving into abstraction. Her works, which tackle themes of race, sexuality, and trauma, use incompleteness to reflect the instability of identity and memory.

In The Painter (1994), she portrays a young girl with smudged features, her body seemingly dissolving into the background. The brushstrokes are loose, the details blurred, leaving her identity in flux.

This unfinished quality is intentional—it mirrors the instability of memory, the fragility of childhood, and the shifting nature of self-perception. For Dumas, the act of leaving a face half-formed is an act of storytelling in itself, it acknowledges that identity is never fixed but always evolving.

Serge Attukwei Clottey

Ghanaian artist Serge Attukwei Clottey works with discarded plastic containers, cutting them into fragments and reassembling them into large-scale tapestries. His “Afrogallonism” movement critiques environmental waste and colonial economic structures. By deliberately leaving gaps and irregularities in his assemblages, Clottey emphasizes the incomplete nature of historical narratives and the need for collective reconstruction.

His Yellow Brick Road (2018) is a sprawling tapestry made from cut-up plastic containers, stitched together into a patchwork of fragmented forms. For Serge Attukwei Clottey, this signifies the history of migration and home. The gaps and irregularities in his assemblage highlight the incomplete nature of African histories—particularly those affected by colonialism and environmental destruction.

His work is both personal and political, a reminder that history, like his stitched-together plastic, is something we must constantly repair and reclaim.

Peju Alatise

Peju Alatise is a Nigerian artist whose multidisciplinary works often focus on the complexities of womanhood, identity, and societal constraints. Her installation Flying Girls (2016) tells the story of Sim, a fictional young girl trapped in domestic servitude who dreams of escape. The piece features a group of faceless, winged girls made from fiberglass and resin, their forms appearing incomplete—caught between earthly struggles and the possibility of flight.

The rough, almost unfinished surfaces of the figures aren’t just aesthetic choices—they symbolize the silencing of young girls in patriarchal societies. Her use of incompleteness isn’t just about artistic technique—it’s about the fragmented realities that many women in Nigeria and beyond endure. The unfinished wings on her figures whisper of hope, of a future where the story continues beyond the confines of societal oppression.

The power of unfinished art lies in its ability to keep the conversation open. It resists closure, rejects definitive narratives, and forces the viewer to participate in meaning-making. For contemporary African artists, incompleteness is not just an aesthetic choice but a profound commentary on history, identity, and memory.

As African art continues to gain global recognition, this embrace of the unfinished serves as a reminder that history is not linear, identity is not static, and the act of storytelling is never truly complete. Perhaps, in the end, what is left unfinished speaks the loudest.